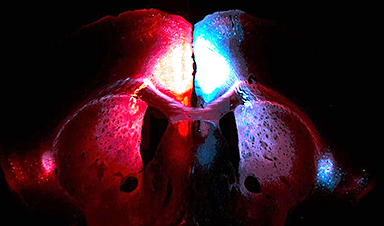

A multidisciplinary team at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine has developed a breakthrough nanodrug platform that may prove beneficial for rapid, targeted therapeutic hypothermia after traumatic brain injury (TBI).

Their work, published in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces, demonstrates that intranasal nanovanilloids can lower brain temperature by 2.0° C to 3.6° C for up to three hours in pre-clinical models. The results offer a promising new approach for protecting the brain at the point of injury.

“This work exemplifies how nanotechnology and neuroscience principles can be applied together to create therapeutic solutions for critical medical problems that have the potential of saving human lives,” said Sylvia Daunert, Ph.D., Lucille P. Markey Chair in Biochemistry and Molecular Biology and director at the Dr. John T. Macdonald Foundation Biomedical Nanotechnology Institute (BioNIUM), one of the study’s lead investigators.

Study Overview: From Chemistry to Clinical Potential

Vanilloids are natural compounds that activate the TRPV1 receptor, which is involved in pain, inflammation and body temperature regulation. The Miller School researchers created nanovanilloids using three cooling compounds: rinvanil, arvanil and olvanil. They used a special process that mixes the drug in alcohol with water while applying sound waves, which helps the particles form and stay evenly sized. Tests showed these particles are very small (all smaller than 200 nanometers), consistent in size and can stay stable for a long time at room temperature.

Importantly, these particles don’t need any extra carriers or coatings. The drug itself forms the particle. This means more medicine can be delivered safely and easily through the nose to reach the brain in a faster and more targeted manner.

The team checked if the nanovanilloids were safe for cells and didn’t cause stress or damage. They found that the particles didn’t harm cell health or increase stress levels. To make sure the nanovanilloid drugs worked as intended, they ran tests showing that the particles activated the target receptor, TRPV1, which is needed to trigger cooling in the brain.

Why the intranasal route?

Delivering the medicine through the nose lets it reach the brain quickly and avoids being filtered out by the body’s usual barriers. This means the treatment works faster and needs a smaller dose compared to giving it through an IV. The research team used a custom designed, 3D-printed spray nozzle to make sure the nanodrug was spread evenly and gently inside the nose.

The researchers also pointed out that similar nasal spray devices are already used for other brain medicines. These devices can be made safely and consistently by following standard manufacturing and quality controls.

Using the device, the team administered nanovanilloids and found:

• Nano-olvanil reduced head temperature by about 2 °C for more than 100 minutes for pre-clinical models with no injury.

• Nano-rinvanil achieved a 3.6 °C drop in brain temperature in pre-clinical models with moderate TBI, with core body temperature remaining stable. That indicated targeted brain cooling, and researchers confirmed no liver or kidney toxicity.

Implications for Patient Care

• Prehospital neuroprotection: Enables rapid brain cooling at the scene or during transport for TBI, spinal cord injury, stroke or heat-related illness.

• Targeted therapy: Localized cooling minimizes systemic side effects, a major limitation of traditional hypothermia methods.

• Scalable platform: The carrier-free nano-assembly approach can be adapted for other hydrophobic drugs, broadening its impact on acute neurological care.

“This approach offers a new pathway to protect the brain during the most critical window, with the potential to improve survival and recovery for patients,” said lead investigator Helen Bramlett, Ph.D., professor of neurological surgery at the Miller School and The Miami Project to Cure Paralysis.

Next Steps

The Miller School researchers plan to advance this technology toward clinical translation, including dose optimization, device compatibility and human factors testing. Their work sets the stage for innovative, patient-first neuroprotection strategies that could be deployed outside hospital settings.

“In my opinion, these results mark one of the most important technological developments in therapeutic hypothermia and targeted temperature management research over the past 30 years,” said W. Dalton Dietrich, Ph.D., scientific director of The Miami Project and professor of neurological surgery and senior associate dean for team science at the Miller School.

“It is important to highlight that the developed technology stems from a team science approach, and that without a multidisciplinary team of scientists, complex problems like this cannot be solved,” Dr. Daunert said.

The Miller School Research Team

The research team was led by Dr. Daunert, Dr. Dietrich, Dr. Bramlett and Sapna Deo, Ph.D., professor of biochemistry and molecular biology at the Miller School.

Other key contributors included:

• Emre Dikici, Ph.D., senior scientist and director of the Bionanotechnology Laboratory

• Alexia Kafkoutsou, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

• Jorge David Tovar, a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology

• Juliana Sànchez, M.D., assistant scientist at the Miami Project to Cure Paralysis

News

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

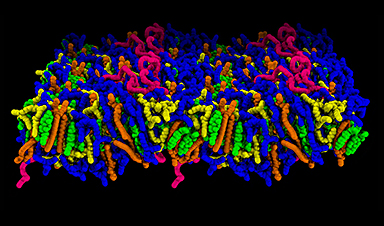

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]