Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs.

Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising again as antibiotic-resistant infections become an increasing threat to public health. Even so, progress in the field has been slow. Most research has relied on naturally occurring phages because traditional engineering methods are time consuming and difficult, limiting the development of customized therapeutic viruses.

A Fully Synthetic Phage Engineering Breakthrough

In a new PNAS study, scientists from New England Biolabs (NEB) and Yale University describe the first fully synthetic system for engineering bacteriophages that target Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an antibiotic-resistant bacterium that poses a serious global health concern. The work is powered by NEB's High-Complexity Golden Gate Assembly (HC-GGA) platform, which allows phages to be designed and built using DNA sequence information rather than physical virus samples.

Using this approach, the researchers constructed a P. aeruginosa phage from 28 synthetic DNA fragments. They then altered the virus by introducing point mutations along with DNA insertions and deletions. These changes allowed the team to modify which bacteria the phage could infect by swapping tail fiber genes and to add fluorescent reporters that made infections visible as they happened.

"Even in the best of cases, bacteriophage engineering has been extremely labor-intensive. Researchers spent entire careers developing processes to engineer specific model bacteriophages in host bacteria," reflects Andy Sikkema, the paper's co-first author and Research Scientist at NEB. "This synthetic method offers technological leaps in simplicity, safety, and speed, paving the way for biological discoveries and therapeutic development."

Building Phages From Digital DNA

NEB's Golden Gate Assembly platform makes it possible to assemble a complete phage genome outside the cell using synthetic DNA, with all planned genetic changes included from the start. Once assembled, the genome is introduced into a safe laboratory strain where it becomes an active bacteriophage.

This process removes many long-standing barriers in phage research. Scientists no longer need to maintain collections of fragile phage isolates or rely on specialized host bacteria, which is especially challenging for phages that infect dangerous human pathogens. The method also avoids the repeated screening and step-by-step genetic editing required by approaches that modify phages inside living cells.

Why Golden Gate Assembly Matters

Compared with DNA assembly techniques that use fewer but longer fragments, Golden Gate Assembly works with shorter DNA segments. These shorter pieces are easier to prepare, less harmful to host cells, and less likely to contain errors. The method is also more tolerant of repeated sequences and extreme GC content, features that are common in many phage genomes.

By simplifying the engineering process and expanding what can be built, the Golden Gate method greatly broadens the possibilities for scientists working to develop bacteriophages as tools to combat antibiotic resistance.

Collaboration Drives New Applications

The development of this rapid synthetic phage engineering approach required close collaboration between NEB scientists and bacteriophage researchers at Yale University. NEB researchers had already created the foundational tools needed to make Golden Gate Assembly reliable for large DNA targets made from many fragments. Yale researchers recognized the potential of these tools and initiated a partnership to explore more ambitious uses.

The method was first refined using a well-studied model virus, Escherichia coli phage T7. Since then, collaborative teams have expanded the approach to include non model bacteriophages that target highly antibiotic-resistant bacteria.

A related study using the Golden Gate method to build high GC content Mycobacterium phages was published in PNAS in November 2025 in collaboration with the Hatfull Lab at the University of Pittsburgh and Ansa Biotechnologies. In another project, researchers from Cornell University worked with NEB to develop synthetically engineered T7 bacteriophages that function as biosensors capable of detecting E. coli in drinking water, described in a December 2025 ACS study.

"My lab builds 'weird hammers' and then looks for the right nails," said Greg Lohman, Senior Principal Investigator at NEB and co-author on the study. "In this case, the phage therapy community told us, 'That's exactly the hammer we've been waiting for.'"

Reference: "A fully synthetic Golden Gate assembly system for engineering a Pseudomonas aeruginosa phiKMV-like phage" by Andrew P. Sikkema, Kaitlyn E. Kortright, Hemaa Selvakumar, Jyot Antani, Benjamin K. Chan, Matthew Davidson, Max Hopkins, Benjamin Newman, Vladimir Potapov, Cecilia A. Silva-Valenzuela, S. Kasra Tabatabaei, Robert McBride, Paul E. Turner and Gregory J. S. Lohman, 23 January 2026, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2525963123

News

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

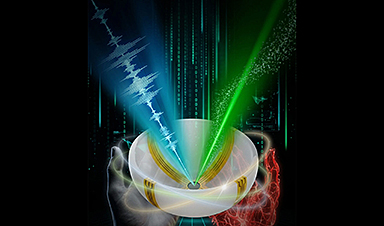

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]

Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D. By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to [...]

Brain waves could help paralyzed patients move again

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs remain healthy, and the brain continues to function normally. The loss of [...]

Scientists Discover a New “Cleanup Hub” Inside the Human Brain

A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste. How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain’s lymphatic drainage [...]

New Drug Slashes Dangerous Blood Fats by Nearly 40% in First Human Trial

Scientists have found a way to fine-tune a central fat-control pathway in the liver, reducing harmful blood triglycerides while preserving beneficial cholesterol functions. When we eat, the body turns surplus calories into molecules called [...]

A Simple Brain Scan May Help Restore Movement After Paralysis

A brain cap and smart algorithms may one day help paralyzed patients turn thought into movement—no surgery required. People with spinal cord injuries often experience partial or complete loss of movement in their arms [...]

Plant Discovery Could Transform How Medicines Are Made

Scientists have uncovered an unexpected way plants make powerful chemicals, revealing hidden biological connections that could transform how medicines are discovered and produced. Plants produce protective chemicals called alkaloids as part of their natural [...]

Scientists Develop IV Therapy That Repairs the Brain After Stroke

New nanomaterial passes the blood-brain barrier to reduce damaging inflammation after the most common form of stroke. When someone experiences a stroke, doctors must quickly restore blood flow to the brain to prevent death. [...]

Analyzing Darwin’s specimens without opening 200-year-old jars

Scientists have successfully analyzed Charles Darwin's original specimens from his HMS Beagle voyage (1831 to 1836) to the Galapagos Islands. Remarkably, the specimens have been analyzed without opening their 200-year-old preservation jars. Examining 46 [...]