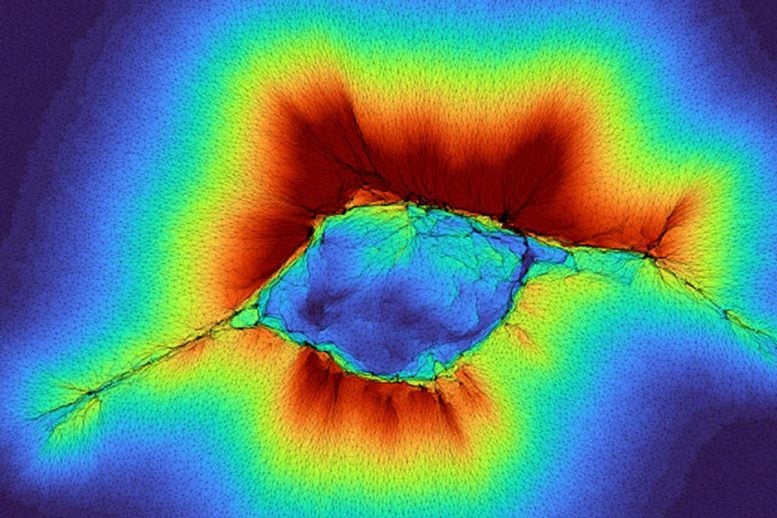

Groups of normal cbiells can sense far into their surroundings, helping explain cancer cell migration. Understanding this ability could lead to new ways to limit tumor spread.

The tale of the princess and the pea describes someone so sensitive that she can detect a single pea beneath layers of bedding. In the biological world, certain cells show a similar heightened sensitivity. Cancer cells, in particular, have an extraordinary ability to detect and respond to their surroundings far beyond their immediate environment.

Now, scientists have discovered that even normal cells can achieve this extended sensing ability—by working together.

A study published in PNAS by engineers at Washington University in St. Louis reveals new insights into how cells perceive what lies beyond their immediate environment. These findings deepen understanding of cancer cell migration and could help identify new molecular targets to halt tumor spread.

How cells extend their sensing range

Amit Pathak, professor of mechanical engineering and materials science at the McKelvey School of Engineering, described this process as "depth mechano-sensing"—the ability of cells to perceive structures beneath the surfaces they adhere to. In earlier research, Pathak and his team discovered that abnormal cells with "high front-rear polarity" (a feature typical of cells in motion) can detect their surroundings up to 10 microns beyond the layer they are attached to.

This extended sensing occurs as the cell reshapes the surrounding fibrous collagen, allowing it to probe deeper into the extracellular matrix (ECM) and "feel" what lies ahead—whether a dense tumor, soft tissue, or bone. A single abnormal cell can gauge the stiffness of the ECM and navigate based on this mechanical feedback.

Collective sensing among normal cells

The new research shows that a collective of epithelial cells, found on the surface of tissue, can do the same and then some, working together to muster enough force to "feel" through the fibrous collagen the layer as far as 100 microns away.

"Because it's a collective of cells, they are generating higher forces," said Pathak, who authored the research along with PhD student Hongsheng Yu.

According to their models, this occurs in two distinct phases of cell clustering and migration. What those clustering cells "feel" will impact migration and dispersal.

Implications for cancer research and treatment

The extra sensing power of cancer cells means that they can get out of the tumor environment and evade detection, migrating freely thanks to their enhanced sense of what's ahead, even in a soft environment. Researchers' next step will be understanding how that works, and if certain regulators allow for the range. Those regulators could be potential targets for cancer therapy. If a cancer cell can't "feel" its way forward, its toxic spread may be put in check.

Reference: "Emergent depth-mechanosensing of epithelial collectives regulates cell clustering and dispersal on layered matrices" by Hongsheng Yu and Amit Pathak, 11 September 2025, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2423875122

Funding for this research was provided by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) (R35GM128764) and National Science Foundation, Civil, Mechanical and Manufacturing Innovation (2209684).

News

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]