Consciousness may emerge not from code, but from the way living brains physically compute.

Discussions about consciousness often stall between two deeply rooted viewpoints. One is computational functionalism, which holds that cognition can be fully explained as abstract information processing. According to this view, if a system has the right functional organization (regardless of the material it runs on), consciousness should emerge. The opposing view, biological naturalism, argues that consciousness cannot be separated from the unique features of living brains and bodies. From this perspective, biology is not just a carrier of cognition, it is a core part of what cognition is. Both positions capture important truths, but their ongoing standoff suggests that an essential element is missing.

A Third Perspective on How Brains Compute

In our new paper, we propose an alternative framework called biological computationalism. The term is intentionally provocative, but also meant to clarify the debate. Our central argument is that the standard model of computation is either broken or poorly aligned with how real brains function. For many years, it has been tempting to assume that brains compute in much the same way traditional computers do, as if cognition were software running on neural hardware. However, brains do not operate like von Neumann machines, and forcing that analogy leads to strained metaphors and fragile explanations. To seriously understand how brains compute, and what it would take to create minds in other substrates, we need to expand our definition of what computation actually means.

Biological computation, as we define it, has three key characteristics.

Hybrid Computation in the Living Brain

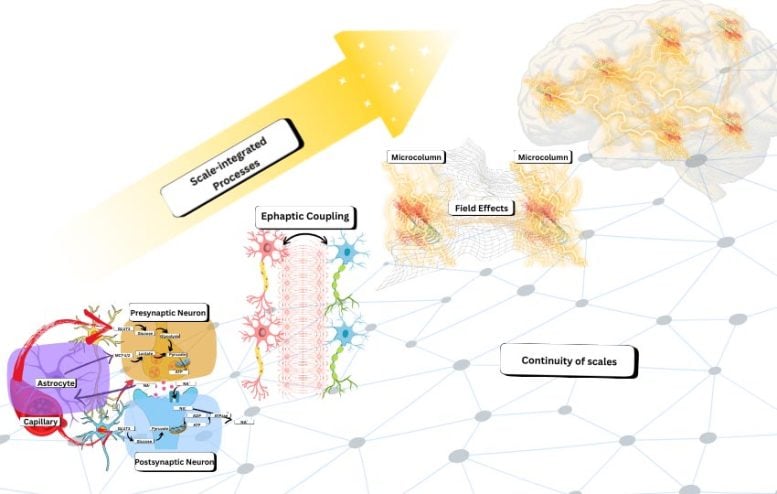

First, biological computation is hybrid. It blends discrete events with continuous processes. Neurons fire spikes, synapses release neurotransmitters, and neural networks shift between event-like states. At the same time, these events unfold within constantly changing physical environments that include voltage fields, chemical gradients, ionic diffusion, and time-varying conductances. The brain is neither purely digital nor simply analog. Instead, it operates as a layered system in which continuous dynamics influence discrete events, and discrete events reshape the surrounding continuous processes through ongoing feedback.

Why Brain Computation Cannot Be Separated by Scale

Second, biological computation is scale-inseparable. In conventional computing, it is usually possible to draw a clear boundary between software and hardware, or between a functional description and its physical implementation. In the brain, that boundary does not exist. There is no clean point where one can say, here is the algorithm, and over there is the physical machinery that carries it out. Instead, causal interactions span many levels at once, from ion channels to dendrites to neural circuits to whole-brain dynamics. These levels do not behave like neatly stacked modules. In biological systems, altering the so-called implementation also alters the computation itself, because the two are tightly intertwined.

Energy Constraints Shape Intelligence

Third, biological computation is metabolically grounded. The brain operates under strict energy limits, and those limits influence its organization at every level. This is not a minor engineering detail. Energy constraints affect what the brain can represent, how it learns, which patterns remain stable, and how information is coordinated and routed. From this perspective, the tight coupling across scales is not unnecessary complexity. It is an energy optimization strategy that supports flexible and resilient intelligence under severe metabolic constraints.

When the Algorithm Is the Physical System

Together, these three features lead to a conclusion that may feel unsettling to anyone used to classical ideas about computation. In the brain, computation is not abstract symbol manipulation. It is not simply a matter of moving representations according to formal rules while treating the physical medium as "mere implementation." In biological computation, the algorithm is the substrate. The physical organization does not just enable computation, it constitutes it. Brains do not merely run programs. They are specific kinds of physical processes that compute by unfolding through time.

Limits of Current AI Models

This perspective also exposes a limitation in how contemporary artificial intelligence is often described. Even highly capable AI systems primarily simulate functions. They learn mappings from inputs to outputs, sometimes with impressive generalization, but the underlying computation remains a digital procedure running on hardware designed for a very different style of processing. Brains, in contrast, carry out computation in physical time. Continuous fields, ion flows, dendritic integration, local oscillatory coupling, and emergent electromagnetic interactions are not just biological "details" that can be ignored when extracting an abstract algorithm. In our view, these processes are the computational primitives of the brain. They are what allow real-time integration, robustness, and adaptive control.

Not Biology Only, But Biology Like Computation

This does not mean we believe consciousness is exclusive to carbon-based life. We are not making a "biology or nothing" claim. Our argument is more precise. If consciousness (or mind-like cognition) depends on this particular kind of computation, then it may require biological-style computational organization, even when implemented in new substrates. The critical question is not whether a system is literally biological, but whether it instantiates the right kind of hybrid, scale-inseparable, metabolically (or more generally energetically) grounded computation.

Rethinking the Goal of Synthetic Minds

This shift has major implications for efforts to build synthetic minds. If brain computation cannot be separated from its physical realization, then simply scaling up digital AI may not be enough. This is not because digital systems cannot become more capable, but because capability alone does not capture what matters. The deeper risk is that we may be optimizing the wrong target by refining algorithms while leaving the underlying computational framework unchanged. Biological computationalism suggests that creating truly mind-like systems may require new kinds of physical machines, ones in which computation is not neatly divided into software and hardware, but spread across levels, dynamically linked, and shaped by real-time physical and energy constraints.

So if the goal is something like synthetic consciousness, the central question may not be, "What algorithm should we run?" Instead, it may be, "What kind of physical system must exist for that algorithm to be inseparable from its own dynamics?" What features are required, including hybrid event-field interactions, multi-scale coupling without clean interfaces, and energetic constraints that shape inference and learning, so that computation is not an abstract layer added on top, but an intrinsic property of the system itself?

That is the shift biological computationalism calls for. It moves the challenge away from finding the right program and toward identifying the right kind of computing matter.

Reference: "On biological and artificial consciousness: A case for biological computationalism" by Borjan Milinkovic and Jaan Aru, 17 December 2025, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews.

DOI: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2025.106524

News

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

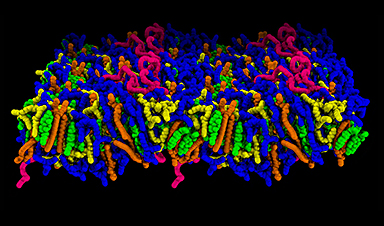

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

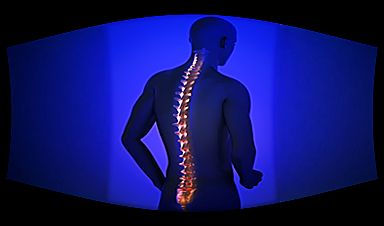

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]