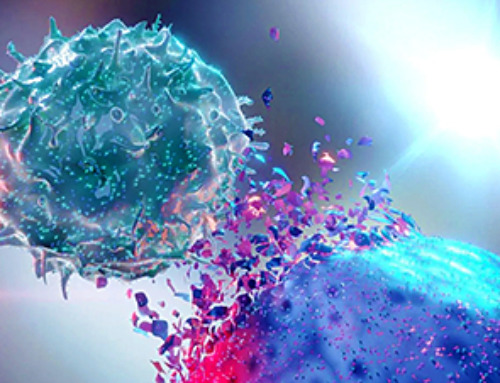

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma.

Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a discovery that could eventually point to a new way to treat this aggressive brain cancer.

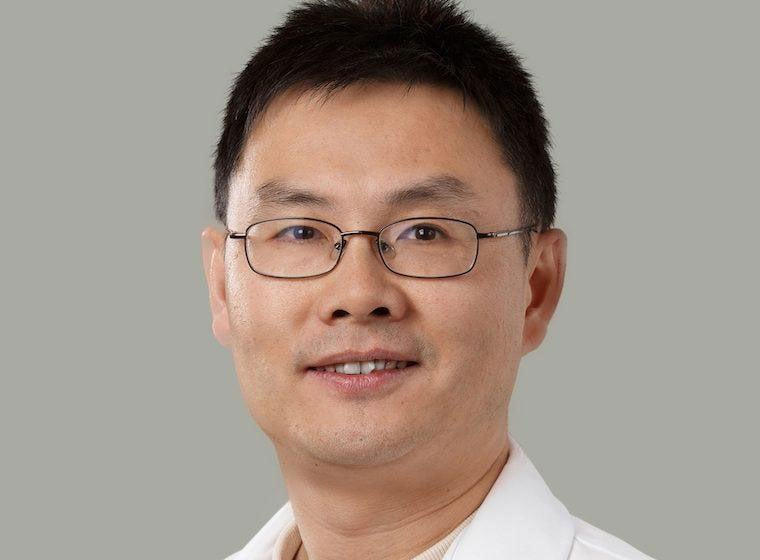

The finding comes from the lab of Hui Li, PhD, who previously identified the "oncogene" that helps drive glioblastoma. In a new study published in Science Translational Medicine, Li reports that the newly identified compound blocked the gene's activity in both cell samples and laboratory mice. In the mouse experiments, the molecule worked without causing harmful side effects.

The research is still at an early stage, and the team emphasizes that much more work is needed before the approach could be considered for patients. Even so, Li says the results hint at something especially important for glioblastoma: slowing a tumor that spreads by infiltrating healthy brain tissue rather than staying in one clearly defined mass.

"Glioblastoma is a devastating disease. Essentially, no effective therapy exists," said Li, of the University of Virginia School of Medicine's Department of Pathology. "What's novel here is that we're targeting a protein that GBM cells uniquely depend on, and we can do it with a small molecule that has clear in vivo activity. To our knowledge, this pathway hasn't been therapeutically exploited before."

About Glioblastoma

Glioblastoma grows quickly and is almost always fatal. After diagnosis, average survival is about 15 months, and more than 14,000 Americans are diagnosed each year. Doctors often begin with surgery, but the cancer spreads through brain tissue in a way that makes complete removal extremely difficult.

Li hopes this line of work can help fill that gap by going after a specific genetic driver. In 2020, his team pinpointed the oncogene, a cancer-causing gene, behind glioblastoma. The gene, AVIL, normally helps cells maintain their size and shape, but the researchers found it can be pushed into an overactive state by a variety of factors, setting the stage for cancer cells to form and spread.

Earlier experiments showed that blocking AVIL activity could wipe out glioblastoma cells in laboratory mice without harming healthy cells. The problem was practicality: the method used to prove that point in the lab was not suitable for people. That challenge is what sent the researchers searching for a molecule that could interrupt the gene's harmful effects in a drug-like way.

Finding a Promising Molecule

Their pursuit has confirmed the role of AVIL in glioblastoma. The researchers found that the protein the gene produces is hardly found in the healthy human brain but is abundant in patients with glioblastoma.

The scientists used a technique called "high-throughput screening" to quickly and efficiently evaluate many compounds for their potential to block AVIL activity. The molecule they have found appears to affect only tumor cells, sparing healthy brain tissue. Further, the molecule can cross the brain's protective barrier that keeps out many potential treatments for neurological diseases.

Before the compound could become available for patients, much additional research will need to be done to optimize the molecule for use in people. If all goes according to plan, the resulting drug would then be tested extensively in human volunteers before the federal Food and Drug Administration decides whether it is sufficiently safe and effective to be offered as a treatment.

While there is much more work to be done, Li and his colleagues are excited by the promise of their latest findings.

"GBM patients desperately need better options. Standard therapy hasn't fundamentally changed in decades, and survival remains dismal," he said. "Our goal is to bring an entirely new mechanism of action into the clinic — one that targets a core vulnerability in glioblastoma biology."

Reference: "A first-in-class small-molecule inhibitor targeting AVIL exhibits safety and antitumor efficacy in preclinical models of glioblastoma" by Zhongqiu Xie, Pawel Ł. Janczyk, Robert Cornelison, Sarah Lynch, Martyna Glowczyk-Gluc, Becky Leifer, Yiwei Wang, Philip Hahn, Johnathon D. Dooley, Adelaide Fierti, Xinrui Shi, Yiyu Zhang, Tingxuan Li, Qiong Wang, Zhi Zhang, Laine Marrah, Angela Koehler, James W. Mandell, Michael Hilinski and Hui Li, 28 January 2026, Science Translational Medicine.

DOI: 10.1126/scitranslmed.adt1211

The research was supported by the National Institutes of Health, grants R01CA240601 and R01CA269594, and by the Ben & Catherine Ivy Foundation.

Li has founded a company, AVIL Therapeutics, to develop AVIL inhibitors. He and Xie also have obtained a patent related to the approach.

News

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

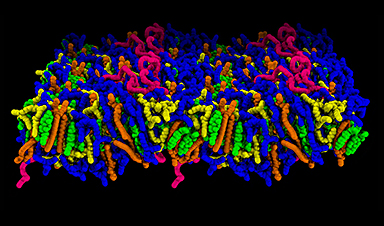

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]

Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D. By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to [...]

Brain waves could help paralyzed patients move again

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs remain healthy, and the brain continues to function normally. The loss of [...]

Scientists Discover a New “Cleanup Hub” Inside the Human Brain

A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste. How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain’s lymphatic drainage [...]