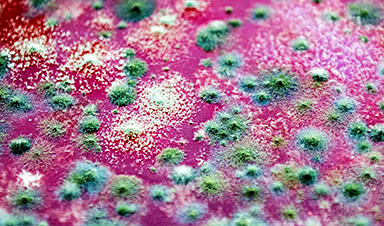

A deadly, drug-resistant hospital fungus may finally have a weakness—and scientists think they’ve found it.

Researchers have identified a genetic process that could open the door to new treatments for a dangerous fungal infection that has repeatedly forced hospital intensive care units to close. The discovery offers fresh hope against a pathogen that has been difficult to control and even harder to treat.

Candida auris poses a serious threat to people who are already critically ill, making hospitals particularly vulnerable to outbreaks. Although the fungus can exist harmlessly on the skin of many people, patients who rely on ventilators face a much higher risk of infection. Once it takes hold, the disease kills around 45 per cent of those infected and can withstand every major class of antifungal medication. This combination has made it extremely challenging to eliminate from hospital wards once it spreads.

A global health threat on the rise

Candida auris was first identified in 2008, and scientists still do not know where it originally came from. Since its discovery, outbreaks have been reported in more than 40 countries, including the UK. The fungus, also known as Candidozyma auris, is now recognized as a global health threat and appears on the World Health Organization’s critical priority fungal pathogens list. In the UK, case numbers have continued to climb over time.

Studying infection in a living host

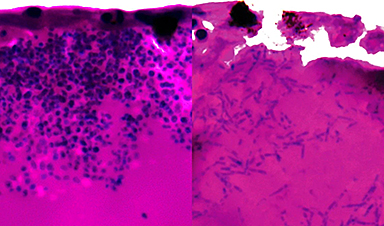

For the first time, a team at the University of Exeter has closely examined how Candida auris activates its genes during infection using an innovative experimental model based on fish larvae. The research was published in the Nature portfolio journal Communications Biology and received support from Wellcome, the Medical Research Council (MRC), and the National Center for Replacement, Reduction and Refinement (NC3Rs).

The results suggest a promising path toward identifying a biological target that could be used to develop new antifungal drugs or adapt existing ones, provided the same genetic activity occurs during infection in humans.

The work was co-led by NIHR Clinical Lecturer Hugh Gifford from the University of Exeter’s MRC Center for Medical Mycology (CMM). He said: “Since it emerged, Candida auris has wreaked havoc where it takes hold in hospital intensive care units. It can be deadly for vulnerable patients, and health trusts have spent millions on the difficult job of eradication. We think our research may have revealed an Achilles heel in this lethal pathogen during active infection, and we urgently need more research to explore whether we can find drugs that target and exploit this weakness.”

Why a new model was needed

One long-standing challenge in studying Candida auris is its ability to survive high temperatures. Combined with its unusually strong tolerance to salt, this has led some scientists to speculate that it may have originated in tropical oceans or marine animals. These traits have also made it harder to study using traditional laboratory models.

To overcome this, the Exeter researchers developed a new system using Arabian killifish, whose eggs are able to survive at human body temperature. This allowed the team to observe the infection process in a living host under realistic conditions.

Genetic clues to survival and spread

During the study, the researchers observed that Candida auris can shift into elongated fungal structures called filaments, which may help it search for nutrients inside the host.

They also tracked which genes were turned on and off during infection, highlighting potential weaknesses. Several of the activated genes are involved in producing nutrient pumps that capture iron-scavenging molecules and pull iron into fungal cells. Iron is essential for survival, and this dependence could represent a critical vulnerability.

Co-senior author Dr. Rhys Farrer from the University of Exeter’s MRC Centre for Medical Mycology said: “Until now, we’ve had no idea what genes are active during infection of a living host. We now need to find out if this also occurs during human infection. The fact that we found genes are activated to scavenge iron gives clues to where Candida auris may originate, such as an iron-poor environment in the sea. It also gives us a potential target for new and already existing drugs.”

Hope for future treatments

Dr. Gifford, who also works as a resident physician in intensive care and respiratory medicine at the Royal Devon & Exeter Hospital, emphasized the potential medical impact of the findings. He said: “While there are a number of research steps to go through yet, our finding could be an exciting prospect for future treatment. We have drugs that target iron scavenging activities. We now need to explore whether they could be repurposed to stop Candida auris from killing humans and closing down hospital intensive care units.”

The Arabian killifish larvae model was developed with support from an NC3Rs project grant as an alternative to using mouse and zebrafish models, which are commonly employed to study how pathogens interact with their hosts.

Dr. Katie Bates, NC3Rs Head of Research Funding, said: “This new publication demonstrates the utility of the replacement model to study Candida auris infection and enable unprecedented insights into cellular and molecular events in live infected hosts. This is a brilliant example of how innovative alternative approaches can overcome key limitations of traditional animal studies.”

Reference: “Xenosiderophore transporter gene expression and clade-specific filamentation in Candida auris killifish (Aphanius dispar) infection” 19 December 2025, Communications Biology.

DOI: 10.1038/s42003-025-09321-z

News

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]

Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D. By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to [...]

Brain waves could help paralyzed patients move again

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs remain healthy, and the brain continues to function normally. The loss of [...]

Scientists Discover a New “Cleanup Hub” Inside the Human Brain

A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste. How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain’s lymphatic drainage [...]

New Drug Slashes Dangerous Blood Fats by Nearly 40% in First Human Trial

Scientists have found a way to fine-tune a central fat-control pathway in the liver, reducing harmful blood triglycerides while preserving beneficial cholesterol functions. When we eat, the body turns surplus calories into molecules called [...]

A Simple Brain Scan May Help Restore Movement After Paralysis

A brain cap and smart algorithms may one day help paralyzed patients turn thought into movement—no surgery required. People with spinal cord injuries often experience partial or complete loss of movement in their arms [...]

Plant Discovery Could Transform How Medicines Are Made

Scientists have uncovered an unexpected way plants make powerful chemicals, revealing hidden biological connections that could transform how medicines are discovered and produced. Plants produce protective chemicals called alkaloids as part of their natural [...]

Scientists Develop IV Therapy That Repairs the Brain After Stroke

New nanomaterial passes the blood-brain barrier to reduce damaging inflammation after the most common form of stroke. When someone experiences a stroke, doctors must quickly restore blood flow to the brain to prevent death. [...]

Analyzing Darwin’s specimens without opening 200-year-old jars

Scientists have successfully analyzed Charles Darwin's original specimens from his HMS Beagle voyage (1831 to 1836) to the Galapagos Islands. Remarkably, the specimens have been analyzed without opening their 200-year-old preservation jars. Examining 46 [...]

Scientists discover natural ‘brake’ that could stop harmful inflammation

Researchers at University College London (UCL) have uncovered a key mechanism that helps the body switch off inflammation—a breakthrough that could lead to new treatments for chronic diseases affecting millions worldwide. Inflammation is the [...]

A Forgotten Molecule Could Revive Failing Antifungal Drugs and Save Millions of Lives

Scientists have uncovered a way to make existing antifungal drugs work again against deadly, drug-resistant fungi. Fungal infections claim millions of lives worldwide each year, and current medical treatments are failing to keep pace. [...]