The idea that we might create machines more intelligent than ourselves is not new. Myths and folk stories abound with creations such as the bronze automaton Talos, who patrolled the island of Crete in Greek mythology. These stories reflect a deep, atavistic fear that there could be other minds that bear the same relationship to us as we do to the animals we eat or keep as pets. With the arrival of artificial intelligence, the idea has re-emerged with a vengeance.

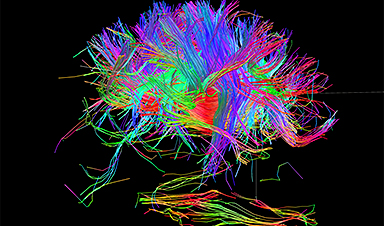

We are condemned to understand new phenomena by analogy with things we already understand, just as the anatomists of old named parts of the brain after fruit and nuts — the amygdala (almonds) and the olives, to name but two. Although Hippocrates, in the fourth century BC, had firmly placed the brain at the centre of human thought and feeling, most early medical authorities had little use for it.

Aristotle thought it was a radiator for cooling the blood. The importance of the brain, for Galen 500 years later, were the fluid cavities — the ventricles — in its centre, and not the tissue of the organ itself. With the rise of scientific method in the 17th century, the brain started to be explained in terms of the latest modern technology. Descartes described the brain and nerves as a series of hydraulic mechanisms. In the 19th century the brain was explained in terms of steam engines and telephone exchanges.

Image Credit: © Courtesy of the USC Laboratory of Neuro Imaging and Athinoula A. Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging, Consortium of the Human Connectome Project

News This Week

Most Plastic in the Ocean Is Invisible—And Deadly

Nanoplastics—particles smaller than a human hair—can pass through cell walls and enter the food web. New research suggest 27 million metric tons of nanoplastics are spread across just the top layer of the North [...]

Repurposed drugs could calm the immune system’s response to nanomedicine

An international study led by researchers at the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus has identified a promising strategy to enhance the safety of nanomedicines, advanced therapies often used in cancer and vaccine treatments, [...]

Nano-Enhanced Hydrogel Strategies for Cartilage Repair

A recent article in Engineering describes the development of a protein-based nanocomposite hydrogel designed to deliver two therapeutic agents—dexamethasone (Dex) and kartogenin (KGN)—to support cartilage repair. The hydrogel is engineered to modulate immune responses and promote [...]

New Cancer Drug Blocks Tumors Without Debilitating Side Effects

A new drug targets RAS-PI3Kα pathways without harmful side effects. It was developed using high-performance computing and AI. A new cancer drug candidate, developed through a collaboration between Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory (LLNL), BridgeBio Oncology [...]

Scientists Are Pretty Close to Replicating the First Thing That Ever Lived

For 400 million years, a leading hypothesis claims, Earth was an “RNA World,” meaning that life must’ve first replicated from RNA before the arrival of proteins and DNA. Unfortunately, scientists have failed to find [...]

Why ‘Peniaphobia’ Is Exploding Among Young People (And Why We Should Be Concerned)

An insidious illness is taking hold among a growing proportion of young people. Little known to the general public, peniaphobia—the fear of becoming poor—is gaining ground among teens and young adults. Discover the causes [...]

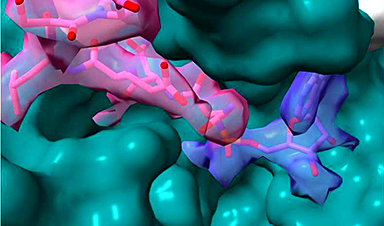

Team finds flawed data in recent study relevant to coronavirus antiviral development

The COVID pandemic illustrated how urgently we need antiviral medications capable of treating coronavirus infections. To aid this effort, researchers quickly homed in on part of SARS-CoV-2's molecular structure known as the NiRAN domain—an [...]

Drug-Coated Neural Implants Reduce Immune Rejection

Summary: A new study shows that coating neural prosthetic implants with the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone helps reduce the body’s immune response and scar tissue formation. This strategy enhances the long-term performance and stability of electrodes [...]

Scientists discover cancer-fighting bacteria that ‘soak up’ forever chemicals in the body

A family of healthy bacteria may help 'soak up' toxic forever chemicals in the body, warding off their cancerous effects. Forever chemicals, also known as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), are toxic chemicals that [...]

Johns Hopkins Researchers Uncover a New Way To Kill Cancer Cells

A new study reveals that blocking ribosomal RNA production rewires cancer cell behavior and could help treat genetically unstable tumors. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular [...]

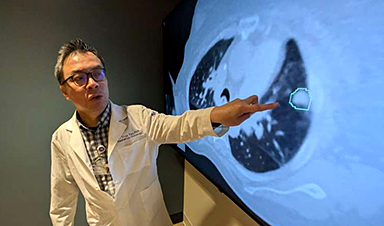

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

Leave A Comment