Scientists have uncovered a way to make existing antifungal drugs work again against deadly, drug-resistant fungi.

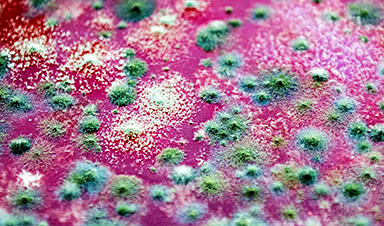

Fungal infections claim millions of lives worldwide each year, and current medical treatments are failing to keep pace. Scientists at McMaster University have now identified a molecule that could help address this growing problem. The compound, known as butyrolactol A, targets Cryptococcus neoformans, a fungus responsible for severe and often fatal disease.

Infections caused by Cryptococcus are especially dangerous. The organism can trigger pneumonia-like symptoms and is well known for its resistance to antifungal drugs. It most often affects people with compromised immune systems, including cancer patients and individuals living with HIV. Other fungi pose similar risks, including Candida auris and Aspergillus fumigatus, both of which have also been designated priority pathogens by the World Health Organization due to their threat to public health.

Despite the seriousness of these infections, treatment options remain extremely limited. Physicians currently rely on just three major classes of antifungal drugs.

Few Drugs, Serious Limitations

The most commonly used option is a group of medications known as amphotericin. Gerry Wright, a professor in McMaster’s Department of Biochemistry and Biomedical Sciences, notes that the drug’s effectiveness comes with significant drawbacks. He jokes that it is often referred to as “amphoterrible” because of the severe toxic side effects it can cause in patients.

“Fungal cells are a lot like human cells, so the drugs that hurt them tend to hurt us too,” he says. “That’s why there are so few options available to patients.”

The two remaining classes of antifungal drugs, azoles and echinocandins, offer far more limited protection, particularly when it comes to treating Cryptococcus infections. According to Wright, azoles only slow fungal growth instead of eliminating the organism. At the same time, Cryptococcus and several other fungi have developed complete resistance to echinocandins, leaving those drugs unable to stop the infection.

Because the development of new antifungal medicines has largely stalled, and existing treatments are losing their effectiveness, researchers are exploring alternative strategies. One promising approach involves the use of compounds known as “adjuvants,” which could help overcome resistance and strengthen the impact of current therapies.

“Adjuvants are helper molecules that don’t actually kill pathogens like drugs do, but instead make them extremely susceptible to existing medicine,” explains Wright, a member of the Michael G. DeGroote Institute for Infectious Disease Research (IIDR).

Turning to Adjuvants

Looking for adjuvants that might better sensitize Cryptococcus to existing antifungal drugs, Wright’s lab screened McMaster’s vast chemical collection for candidate molecules.

Quickly, his team found a hit: butyrolactol A, a known-but-previously-understudied molecule produced by certain Streptomyces bacteria. The researchers found that the molecule could synergize with echinocandin drugs to kill fungi that the drugs alone could not.

But they had no idea how it worked — and almost didn’t bother to find out.

“This molecule was first discovered in the early 1990s, and nobody has ever really looked at it since,” Wright says. “So, when it showed up in our screens, my first instinct was to walk away from it. I thought, ‘it’s a known compound, it kind of looks like amphotericin, it’s just another toxic molecule — not worth our time.’”

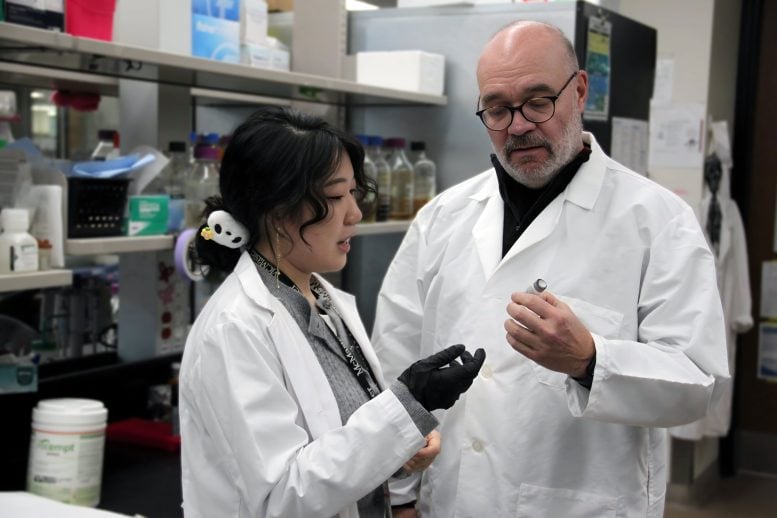

But he credits the determination of postdoctoral fellow Xuefei Chen for changing his mind.

“Early on, this molecule’s activity appeared to be quite good,” says Chen, who works in Wright’s lab. “I felt that if there was even a small chance that it could revive an entire class of antifungal medicine, we had to explore it.”

How the Adjuvant Works

After years of what Wright calls “painstaking sleuthing and detective work” led by Chen, the research team revealed exactly how the adjuvant worked.

Chen discovered that butyrolactol A acts as a plug that clogs up an important protein complex that’s “mission critical” for Cryptococcus — “when it’s jammed, all hell breaks loose,” Wright says. This disturbance renders the fungus completely vulnerable to the drugs that it once resisted.

Working with researchers in the laboratory of McMaster Professor Brian Coombes, also a member of the IIDR, the research team has since shown that butyrolactol A also functions similarly in Candida auris, which gives it broad clinical potential.

Wright says the findings, published recently in the prestigious journal Cell, are more than a decade in the making.

“That first screen that put butyrolactol A on our radar took place in 2014,” he notes. “More than eleven years later, thanks almost entirely to Chen, we have identified a legitimate drug candidate and an entirely new target to attack with other new drugs.”

Reference: “Butyrolactol A enhances caspofungin efficacy via flippase inhibition in drug-resistant fungi” by Xuefei Chen, H. Diessel Duan, Michael J. Hoy, Kalinka Koteva, Michaela Spitzer, Allison K. Guitor, Emily Puumala, Aline A. Fiebig, Guanggan Hu, Bonnie Yiu, Sommer Chou, Zhuyun Bian, Yeseul Choi, Amelia Bing Ya Guo, Wenliang Wang, Sheng Sun, Nicole Robbins, Anna Floyd Averette, Michael A. Cook, Ray Truant, Lesley T. MacNeil, Eric D. Brown, James W. Kronstad, Brian K. Coombes, Leah E. Cowen, Joseph Heitman, Huilin Li and Gerard D. Wright, 31 December 2025, Cell.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.11.036

News

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]