Scientists have developed tiny metal-oxide particles that push cancer cells past their stress limits while sparing healthy tissue.

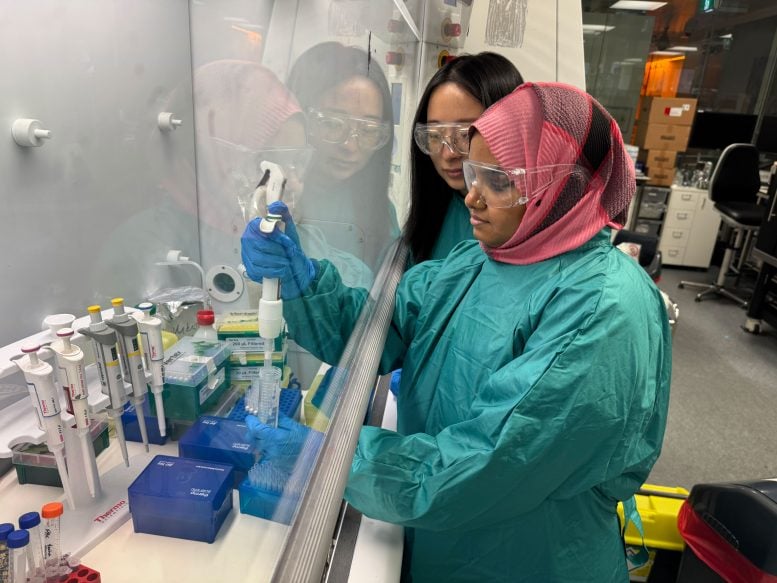

An international team led by RMIT University has developed tiny particles called nanodots, crafted from a metallic compound, that can destroy cancer cells while largely preserving healthy ones.

Although the research is still limited to cell cultures and has not yet been evaluated in animals or humans, the findings suggest a promising new approach for creating cancer treatments that take advantage of vulnerabilities within cancer cells.

These nanodots consist of molybdenum oxide, a material derived from the rare metal molybdenum, which is commonly used in electronics and metal alloys.

According to lead researchers Professor Jian Zhen Ou and Dr. Baoyue Zhang of the School of Engineering, slight adjustments to the particles' chemistry caused them to release reactive oxygen molecules. These unstable oxygen forms can harm vital parts of a cell and initiate cell death.

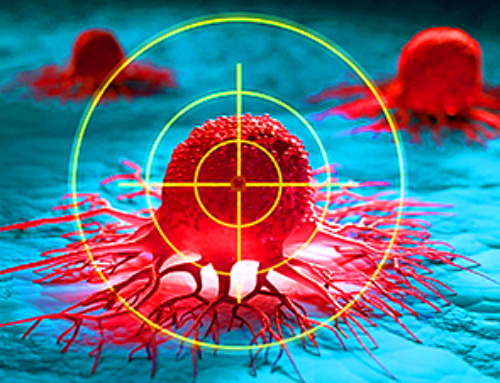

In laboratory experiments, the nanodots eliminated cervical cancer cells at three times the rate observed in healthy cells over a 24-hour period. Notably, they were effective without the need for light, which is uncommon for technologies of this type.

"Cancer cells already live under higher stress than healthy ones," Zhang said.

"Our particles push that stress a little further – enough to trigger self-destruction in cancer cells, while healthy cells cope just fine."

The collaboration involved Dr Shwathy Ramesan at The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health in Melbourne and researchers from institutions in China including Southeast University, Hong Kong Baptist University and Xidian University, with support from the ARC Centre of Excellence in Optical Microcombs (COMBS).

"The result was particles that generate oxidative stress selectively in cancer cells under lab conditions," she said.

How the innovation works

The team adjusted the recipe of the metal oxide, adding tiny amounts of hydrogen and ammonium.

This fine-tuning changed how the particles handled electrons, helping them produce more of the reactive oxygen molecules that drive cancer cells into apoptosis – the body's natural clean-up process for damaged cells.

In another test, the same particles broke down a blue dye by 90 per cent in just 20 minutes, showing how powerful their reactions can be even in darkness.

Most current cancer treatments affect both cancerous and healthy tissue. Technologies that more selectively stress cancer cells could lead to gentler, more targeted therapies.

Because these particles are based on a common metal oxide rather than expensive or toxic noble metals like gold or silver, they could also be cheaper and safer to develop.

Next steps for industry and clinical researchers

The COMBS team at RMIT is continuing this work, with next steps including:

- targeting delivery systems so the particles activate only inside tumors.

- controlling the release of reactive oxygen species to avoid damage to healthy tissue.

- seeking partnerships with biotech or pharmaceutical companies to test the particles in animal models and develop scalable manufacturing methods.

Reference: "Ultrathin Multi-Doped Molybdenum Oxide Nanodots as a Tunable Selective Biocatalyst" by Bao Yue Zhang, Farjana Haque, Shwathy Ramesan, Sanjida Afrin, Muhammad Waqas Khan, Haibo Ding, Xin Zhou, Qijie Ma, Jiaru Zhang, Rui Ou, Md Mohiuddin, Enamul Haque, Yichao Wang, Azmira Jannat, Yumin Li, Robi S. Datta, Kate Fox, Guolang Li, Hujun Jia and Jian Zhen Ou, 3 October 2025, Advanced Science.

DOI: 10.1002/advs.202500643

Organizations that want to partner with RMIT researchers can contact research.partnerships@rmit.edu.au

Funding: Australian Research Council

News

Scientists Discover Why Some COVID Survivors Still Can’t Taste Food Years Later

A new study provides the first direct biological evidence explaining why some people continue to experience taste loss long after recovering from COVID-19. Researchers have uncovered specific biological changes in taste buds that could help [...]

Catching COVID significantly raises the risk of developing kidney disease, researchers find

Catching Covid significantly raises the risk of developing deadly kidney disease, research has shown. The virus was found to increase the chances that patients will develop the incurable condition by around 50 per cent. [...]

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]