Tiny circles of DNA harbor cancer-associated oncogenes and immunomodulatory genes promoting cancer development. They arise during the transformation from pre-cancer to cancer, say Stanford Medicine-led team.

Tiny circles of DNA that defy the accepted laws of genetics are key drivers of cancer formation, according to an international study led by researchers at Stanford Medicine.

The circles, known as extrachromosomal DNA or ecDNA, often harbor cancer-associated genes called oncogenes. Because they can exist in large numbers in a cell, they deliver a super-charged growth signal that can override a cell's natural programming. They also contain genes likely to dampen the immune system's response to a nascent cancer, the researchers found.

"This study has profound implications for our understanding of ecDNA in tumor development," said professor of pathology Paul Mischel, MD. "It shows the power and diversity of ecDNA as a fundamental process in cancer. It has implications for early diagnosis of precancers that put patients at risk, and it highlights the potential for earlier intervention as treatments are developed."

Mischel is one of six senior authors of the research, which was published recently in the journal Nature. Howard Chang, MD, PhD, professor of genetics and the Virginia and D.K. Ludwig Professor in Cancer Research, is also a senior author. Other senior authors include senior staff scientist Thomas Paulson, PhD, from Seattle's Fred Hutchison Cancer Center; assistant professor of pediatrics Sihan Wu, PhD, assistant professor at Children's Medical Center Research Institute at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center; professor of computer science and engineering Vineet Bafna, PhD, from UC San Diego; and professor of cancer prevention and director of the Early Cancer Institute Rebecca Fitzgerald, MD, from the University of Cambridge.

"People with ecDNA in their precancerous cells are 20 to 30 times more likely than others to develop cancer," Chang said. "This is a huge increase, and it means we really need to pay attention to this. Because we also found that some ecDNAs carry genes that affect the immune system, it suggests that they may also promote early immune escape."

A grand challenge

Deciphering ecDNA's role in cancer was one of four Cancer Grand Challenges awarded by the National Cancer Institute and Cancer Research UK in 2022. The grand challenges program was launched to bring together researchers from around the world to tackle complex research topics too daunting for any one group. Mischel was awarded $25 million to lead a team of international researchers to learn more about the circles. But first they had to jettison some key genetic principles that have guided the field for nearly 200 years.

"When we think about how a tumor evolves in a patient and in response to treatment, we think of the branching trees of life proposed by Charles Darwin," Mischel said. "This idea is so powerful that researchers often sequence the DNA from multiple parts of a tumor and draw these trees to learn about its evolution. If a mutation is there at the trunk of the tree and in all of its branches, we assume it is a key driver event in the formation of the tumor; if it is in only some branches, we assume it happened later in tumor development and may not be a good target for drug development."

But these assumptions hinge on the idea that all of a tumor's DNA is neatly contained on chromosomes, which are evenly divided among daughter cells each time a cancer cell divides — ensuring that each new cell gets one, and only one, copy of each chromosome.

In contrast, the tiny ecDNA circles swirl in a dividing cell like bubbles circling a bathtub drain and are portioned willy-nilly between the new daughter cells. One may get nearly all the circles; the other, almost none. As the generations accumulate, the evolutionary tree favored by Darwin begins to look decidedly odd, with the appearance of ecDNA-bearing cells sprinkled among the branches like haphazardly hung Christmas lights.

"Some researchers have looked at the evolutionary trees and decided that, because you see it here, but not there, it must be that ecDNA formation is a late event and probably isn't important when considering treatments," Mischel said. "Our team thought that interpretation was wrong."

Pinpointing a reason

To get to the bottom of the tiny circles, Mischel, Chang and their collaborators turned to a specific example of cancer development — people with a condition known as Barrett's esophagus, which occurs when the cells lining the lower part of the esophagus are damaged by acid reflux and become more like cells lining the intestine than healthy esophageal tissue. About 1% of these people develop esophageal cancer, which is difficult to treat and has a high mortality rate. Because the outcome is so poor, people with Barrett's esophagus are routinely monitored with endoscopies and biopsies of the abnormal tissue. Because of these frequent biopsies, the researchers had access to tissue samples collected both before and after cancers developed.

The researchers assessed the prevalence of ecDNA, and identified the genes they carried, in biopsies from nearly 300 people with Barrett's esophagus or esophageal cancer treated at the University of Cambridge or at Seattle's Fred Hutchison Cancer Center, where individual patients were studied as the cancer developed. They found that the prevalence of ecDNA increased from 24% to 43% in early- versus late-stage esophageal cancer, indicating the continual formation of the DNA circles during cancer progression. More tellingly, they found that 33% of people with Barrett's esophagus who developed esophageal cancer had ecDNA in their precancerous cells. In contrast, only one out of 40 people who didn't develop cancer had cells with ecDNA, and that individual passed away due to another cause.

"The conclusions were remarkable," Mischel said. "We see that ecDNA can arise in these precancerous cells, and that if it is there, the patient is going to get cancer. We also saw the continuous formation of ecDNA as the cancer progresses, indicating that it is advantageous to cancer growth. Finally, we saw that the ecDNA can contain immune-modulatory genes in addition to oncogenes."

"If a gene is carried on ecDNA, it is very likely to be important for cancer," Chang said. "These circles are not only giving us new targets for cancer diagnosis and drug development; they are also teaching us what is important for tumor growth."

What to look at next

The researchers are planning to explore more about how ecDNAs arise in cancer cells and how they work together to make proteins that drive cancer cell growth. They saw that cancers with ecDNA were likely to also have mutations in a protein called p53. Sometimes called "the guardian of the genome," p53 temporarily halts the cell cycle to allow cells to repair damage or mutations to their DNA before beginning to divide.

"We want to learn more about the landscape of ecDNA in precancers and the risks it confers," Mischel said. "We also want to know if we can stop its formation or activity; how to improve our ability to detect their presence; how they affect the immune system; and whether there are opportunities for new, novel therapies. There is much more to learn, and our team is excited to tackle all these issues. But what we do know for certain is that these tiny DNA circles are a very big deal in cancer."

News

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

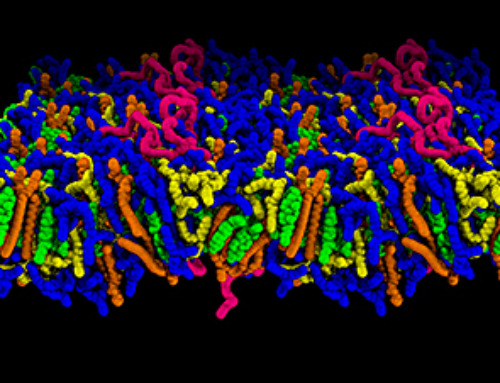

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]

Scientists Develop a New Way To See Inside the Human Body Using 3D Color Imaging

A newly developed imaging method blends ultrasound and photoacoustics to capture both tissue structure and blood-vessel function in 3D. By blending two powerful imaging methods, researchers from Caltech and USC have developed a new way to [...]

Brain waves could help paralyzed patients move again

People with spinal cord injuries often lose the ability to move their arms or legs. In many cases, the nerves in the limbs remain healthy, and the brain continues to function normally. The loss of [...]

Scientists Discover a New “Cleanup Hub” Inside the Human Brain

A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste. How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain’s lymphatic drainage [...]

New Drug Slashes Dangerous Blood Fats by Nearly 40% in First Human Trial

Scientists have found a way to fine-tune a central fat-control pathway in the liver, reducing harmful blood triglycerides while preserving beneficial cholesterol functions. When we eat, the body turns surplus calories into molecules called [...]