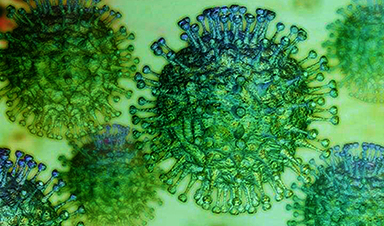

Researchers identify a shared RNA-protein interaction that could lead to broad-spectrum antiviral treatments for enteroviruses.

A new study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), published in Nature Communications, explains how enteroviruses begin reproducing inside human cells. These viruses include those responsible for polio, encephalitis, myocarditis, and the common cold, and they start infection by taking over the cell's own molecular machinery.

The research was led by senior author Deepak Koirala, associate professor of chemistry and biochemistry, along with recent Ph.D. graduate Naba Krishna Das, and it addresses a long-standing gap in understanding this early stage of viral replication. The findings could also help guide the development of antiviral drugs that work against multiple enteroviruses.

"My lab has been really motivated to understand how RNA viruses produce their proteins inside the cell and multiply their genome to make more virus particles," Koirala says. Building on their discovery of a crucial cloverleaf structure in the viral RNA, Koirala's group has now shown how it recruits proteins to assemble the replication complex.

Seeing the bigger picture

Enteroviruses carry a very small RNA genome that must perform two essential tasks. It serves as instructions for making viral proteins and also acts as the template for copying itself to create new virus particles. While most of this compact genome codes for structural components, it also produces a limited set of proteins that are crucial for replication and not found in human cells.

One of these proteins is a combined molecule known as 3CD. One portion (3C) functions like molecular scissors, cutting the long chain of amino acids produced from the viral RNA into separate working proteins. The other portion (3D) acts as an RNA polymerase, the enzyme responsible for copying the viral RNA. Because human cells do not contain this type of polymerase, the virus must supply it on its own.

"We previously determined the structure of the RNA alone, and other groups determined the structure of 3C and 3D, but now we've captured the structure of the RNA and proteins together, so we know how they are interacting," Koirala explains. "We found that it's the 3C domain of 3CD that binds to the RNA in the viral genome, and then it recruits the other components, such as host protein PCBP2, to assemble the replication complex."

The same complex also works as an on-off switch: when 3CD is attached, the virus copies its RNA; when it lets go, the RNA can be read to make proteins instead.

Resolving a debate

Koirala's team used X-ray crystallography to visualize the interactions between the RNA cloverleaf and 3CD. They augmented those observations with isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC), a technique that quantifies the strength of an interaction by measuring the heat released when molecules bind, and biolayer interferometry (BLI), which tracks light interference to gauge binding duration.

The team also settled a debate by showing that two complete 3CD molecules (bringing two RNA polymerases) bind side-by-side on the RNA, rather than forming a single fused pair, as research from another group had suggested. Why two are needed is still a mystery, but the picture is now clear.

New therapeutic targets

Perhaps most exciting, the seven types of enteroviruses the paper investigated all employed a very similar binding mechanism and RNA cloverleaf structure. The extent of this conservation implies the RNA cloverleaf is very important for replication, and any mutations would likely derail it. That means the RNA and RNA-protein interface is likely to be stable over time and across enteroviruses, making it an even more promising drug target—and opening the door to the tantalizing prospect of a "universal" drug targeting all enteroviruses.

Drugs disrupting 3C and 3D activity are already in development, but "now we have another layer to test," Koirala says. "What if we target the RNA, or the RNA-protein interface, so that we break the interaction? That is another opportunity. Now that we have high-resolution structures, you can precisely design drug molecules to target them."

"Viruses are so, so clever. Their entire genome is equivalent to about one mRNA sequence in humans, yet they are so effective," Koirala says. His latest work demonstrates "why we need to investigate this basic science—so that it can be translated into developing drugs targeting pathogens that cause so many harmful diseases."

Reference: "Structural basis for 3C and 3CD recruitment by enteroviral genomes during negative-strand RNA synthesis" by Naba Krishna Das, Alisha Patel, Reem Abdelghani and Deepak Koirala, 21 October 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-64376-0

Funding: U.S. National Science Foundation, NIH/National Institutes of Health

News

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

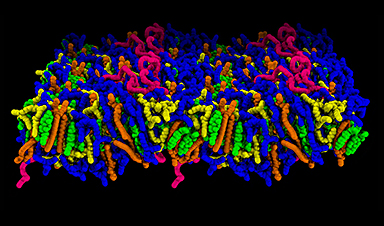

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]