Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized treatments.

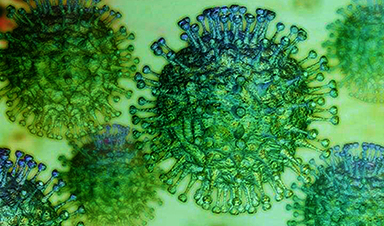

The COVID-19 pandemic highlighted just how differently people can respond to the same infection. Some individuals experience mild symptoms, while others become severely ill. This striking contrast raises an important question. Why would two people infected by the same pathogen have such different outcomes?

Much of the answer lies in differences in genetics (the genes you inherit) and life experience (your environmental, infection, and vaccination history). These influences shape our cells through subtle molecular modifications known as epigenetic changes. These changes do not alter the DNA sequence itself. Instead, they control whether specific genes are turned "on" or "off," helping determine how cells behave and function.

Researchers at the Salk Institute have introduced a comprehensive epigenetic catalog that separates the effects of inherited genetics from those of life experiences across multiple immune cell types. This new cell type-specific database, published in Nature Genetics on January 27, 2026, provides insight into why immune responses vary from person to person and could help guide the development of more precise, personalized treatments.

"Our immune cells carry a molecular record of both our genes and our life experiences, and those two forces shape the immune system in very different ways," says senior author Joseph Ecker, PhD, professor, Salk International Council Chair in Genetics, and Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. "This work shows that infections and environmental exposures leave lasting epigenetic fingerprints that influence how immune cells behave. By resolving these effects cell by cell, we can begin to connect genetic and epigenetic risk factors to the specific immune cells where disease actually begins."

Understanding the Epigenome and Gene Regulation

Every cell in the body contains the same DNA. Even so, cells can look and function very differently depending on their role. This variation is partly explained by epigenetic markers, small chemical tags attached to DNA that help determine which genes are active and which remain silent. The full set of these modifications within a cell is known as its epigenome.

Unlike the fixed DNA sequence, the epigenome is dynamic. Some epigenetic differences are strongly influenced by inherited genetic variation, while others develop over time through life experiences. Immune cells are shaped by both factors. However, until this study, scientists did not know whether inherited and experience-driven epigenetic changes influence immune cells in the same way.

"The debate between nature and nurture is a long-standing discussion in both biology and society," says co-first author Wenliang Wang, PhD, a staff scientist in Ecker's lab. "Ultimately, both genetic inheritance and environmental factors impact us, and we wanted to figure out exactly how that manifests in our immune cells and informs our health."

To explore how genetics and life experiences affect immune cell epigenomes, the Salk team analyzed blood samples from 110 individuals with diverse genetic backgrounds and exposure histories. These participants had encountered a range of conditions and exposures, including flu; HIV-1, MRSA, MSSA, and SARS-CoV-2 infections; anthrax vaccination; and exposure to organophosphate pesticides.

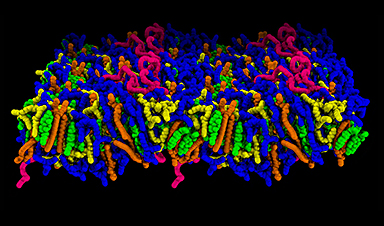

The researchers focused on four major immune cell types. T cells and B cells are responsible for long-term immune memory, while monocytes and natural killer cells respond quickly and more broadly to threats. By examining epigenetic patterns in each cell type, the team assembled a detailed catalog of epigenetic markers, referred to as differentially methylated regions (DMRs).

"We found that disease-associated genetic variants often work by altering DNA methylation in specific immune cell types," says co-first author Wubin Ding, PhD, a postdoctoral fellow in Ecker's lab. "By mapping these connections, we can begin to pinpoint which cells and molecular pathways may be affected by disease risk genes, potentially opening new avenues for more targeted therapies."

Genetic Versus Experience-Driven Epigenetic Changes

A major achievement of the study was distinguishing epigenetic changes tied to inherited genetics (gDMRs) from those linked to life experiences (eDMRs). The team discovered that these two categories tend to cluster in different regions of the epigenome. Genetically influenced gDMRs were more commonly found near stable gene regions, particularly in long-lived T and B cells. In contrast, experience-related eDMRs were concentrated in flexible regulatory regions that help control specific immune responses.

These findings suggest that inherited genetics helps establish stable, long-term immune programs, while life experiences fine-tune more adaptable and context-specific responses. Further studies will be needed to clarify how these influences ultimately affect immune performance and disease outcomes.

"Our human population immune cell atlas will also be an excellent resource for future mechanistic research on both infectious and genetic diseases, including diagnoses and prognosis," says co-first author Manoj Hariharan, PhD, a senior staff scientist in Ecker's lab. "Often, when people become sick, we are not immediately sure of the cause or potential severity—the epigenetic signatures we developed offer a road map to classify and assess these situations."

Predicting Disease Risk and Personalizing Treatment

The results underscore how both nature and nurture shape immune cell identity and overall immune system behavior. The new catalog also provides a starting framework for more personalized approaches to prevention and treatment.

Ecker explains that as more patient samples are added, the database could eventually help predict how individuals might respond to infections. For example, if sufficient COVID-19 patient data are included, researchers might find that survivors share a common protective eDMR. Clinicians could then examine whether newly infected patients possess this same epigenetic marker. If not, scientists might target related regulatory mechanisms to improve outcomes.

"Our work lays the foundation for developing precision prevention strategies for infectious diseases," says Wang. "For COVID-19, influenza, or many other infections, we may one day be able to help predict how someone may react to an infection, even before exposure, as cohorts and models continue to expand. Instead, we can just use their genome to predict the ways the infection will impact their epigenome, then predict how those epigenetic changes will influence their symptoms."

Reference: "Genetics and environment distinctively shape the human immune cell epigenome" by Wenliang Wang, Manoj Hariharan, Wubin Ding, Anna Bartlett, Cesar Barragan, Rosa Castanon, Ruoxuan Wang, Vince Rothenberg, Haili Song, Joseph R. Nery, Andrew Aldridge, Jordan Altshul, Mia Kenworthy, Hanqing Liu, Wei Tian, Jingtian Zhou, Qiurui Zeng, Huaming Chen, Bei Wei, Irem B. Gündüz, Todd Norell, Timothy J. Broderick, Micah T. McClain, Lisa L. Satterwhite, Thomas W. Burke, Elizabeth A. Petzold, Xiling Shen, Christopher W. Woods, Vance G. Fowler Jr., Felicia Ruffin, Parinya Panuwet, Dana B. Barr, Jennifer L. Beare, Anthony K. Smith, Rachel R. Spurbeck, Sindhu Vangeti, Irene Ramos, German Nudelman, Stuart C. Sealfon, Flora Castellino, Anna Maria Walley, Thomas Evans, Fabian Müller, William J. Greenleaf and Joseph R. Ecker, 27 January 2026, Nature Genetics.

DOI: 10.1038/s41588-025-02479-6

Other authors include Anna Bartlett, Cesar Barragan, Rosa Castanon, Vince Rothenberg, Haili Song, Joseph Nery, Jordan Altshul, Mia Kenworthy, Hanqing Liu, Wei Tian, Jingtian Zhou, Qiurui Zeng, and Huaming Chen of Salk; Andrew Aldridge, Lisa L. Satterwhite, Thomas W. Burke, Elizabeth A. Petzold, and Vance G. Fowler Jr. of Duke University; Bei Wei and William J. Greenleaf of Stanford University; Irem B. Gündüz and Fabian Müller of Saarland University; Todd Norell and Timothy J. Broderick of the Florida Institute for Human and Machine Cognition; Micah T. McClain and Christopher W. Woods of Duke University and Durham Veterans Affairs Medical Center; Xiling Shen of the Terasaki Institute for Biomedical Innovation; Parinya Panuwet, and Dana B. Barr of Emory University; Jennifer L. Beare, Anthony K. Smith, and Rachel R. Spurbeck of Battelle Memorial Institute; Sindhu Vangeti, Irene Ramos, German Nudelman, and Stuart C. Sealfon of Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai; Flora Castellino of the US Department of Health and Human Services; and Anna Maria Walley and Thomas Evans of Vaccitech plc.

The work was supported by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (N6600119C4022) through the US Army Research Office (W911NF-19-2-0185), National Institutes of Health (P50-HG007735, UM1-HG009442, UM1-HG009436, 1R01AI165671), and National Science Foundation (1548562, 1540931, 2005632).

News

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

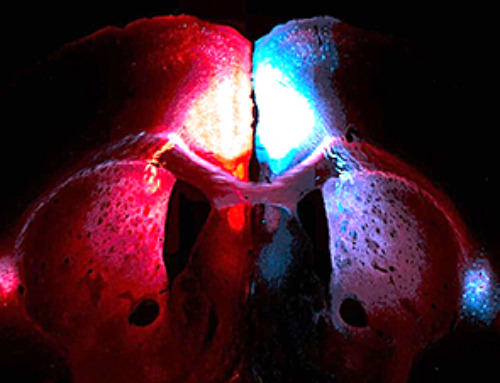

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]

Smaller Than a Grain of Salt: Engineers Create the World’s Tiniest Wireless Brain Implant

A salt-grain-sized neural implant can record and transmit brain activity wirelessly for extended periods. Researchers at Cornell University, working with collaborators, have created an extremely small neural implant that can sit on a grain of [...]