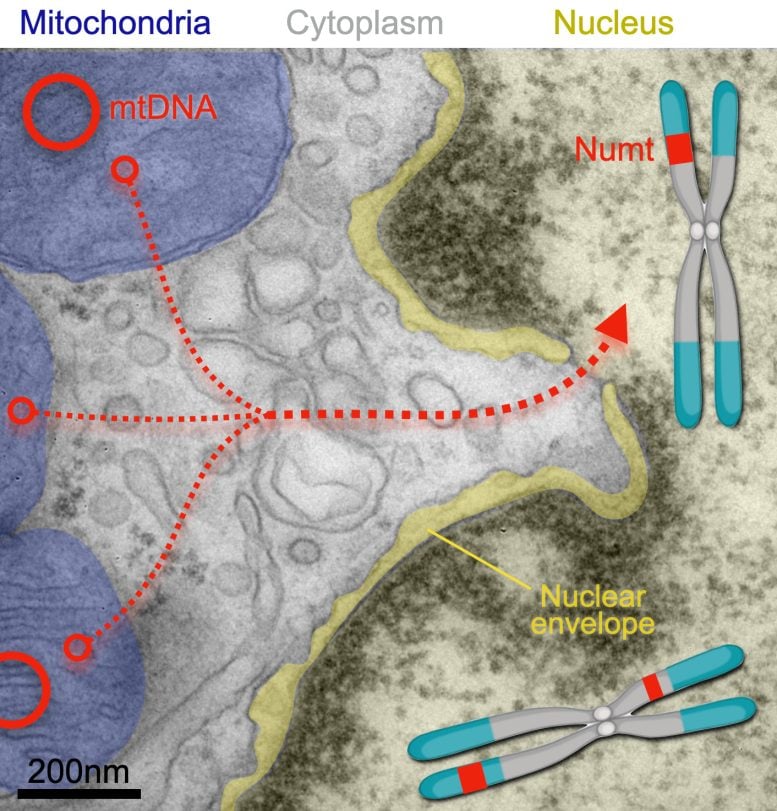

According to the research, these mitochondrial DNA insertions could be linked to early death.

Mitochondria in brain cells frequently insert their DNA into the nucleus, potentially impacting lifespan, as those with more insertions were found to die earlier. Stress appears to accelerate this process, suggesting a new way mitochondria influence health beyond energy production.

As direct descendants of ancient bacteria, mitochondria have always been a little alien. Now a study shows that mitochondria are possibly even stranger than we thought.

Mitochondria in our brain cells frequently fling their DNA into the nucleus, the study found, where the DNA becomes integrated into the cells' chromosomes. And these insertions may be causing harm: Among the study's nearly 1,200 participants, those with more mitochondrial DNA insertions in their brain cells were more likely to die earlier than those with fewer insertions.

"We used to think that the transfer of DNA from mitochondria to the human genome was a rare occurrence," says Martin Picard, mitochondrial psychobiologist and associate professor of behavioral medicine at Columbia University Vagelos College of Physicians and Surgeons and in the Robert N. Butler Columbia Aging Center. Picard led the study with Ryan Mills of the University of Michigan.

"It's stunning that it appears to be happening several times during a person's lifetime, Picard adds. "We found lots of these insertions across different brain regions, but not in blood cells, explaining why dozens of earlier studies analyzing blood DNA missed this phenomenon."

Mitochondrial DNA behaves like a virus

Mitochondria live inside all our cells, but unlike other organelles, mitochondria have their own DNA, a small circular strand with about three dozen genes. Mitochondrial DNA is a remnant from the organelle's forebears: ancient bacteria that settled inside our single-celled ancestors about 1.5 billion years ago.

In the past few decades, researchers discovered that mitochondrial DNA has occasionally "jumped" out of the organelle and into human chromosomes.

"The mitochondrial DNA behaves similar to a virus in that it makes use of cuts in the genome and pastes itself in, or like jumping genes known as retrotransposons that move around the human genome," says Mills.

The insertions are called nuclear-mitochondrial segments—NUMTs ("pronounced new-mites")—and have been accumulating in our chromosomes for millions of years.

"As a result, all of us are walking around with hundreds of vestigial, mostly benign, mitochondrial DNA segments in our chromosomes that we inherited from our ancestors," Mills says.

Mitochondrial DNA insertions are common in the human brain

Research in just the past few years has shown that "NUMTogenesis" is still happening today.

"Jumping mitochondrial DNA is not something that only happened in the distant past," says Kalpita Karan, a postdoc in the Picard lab who conducted the research with Weichen Zhou, a research investigator in the Mills lab. "It's rare, but a new NUMT becomes integrated into the human genome about once in every 4,000 births. This is one of many ways, conserved from yeast to humans, by which mitochondria talk to nuclear genes."

The realization that new inherited NUMTs are still being created made Picard and Mills wonder if NUMTs could also arise in brain cells during our lifespan.

"Inherited NUMTs are mostly benign, probably because they arise early in development and the harmful ones are weeded out," says Zhou. But if a piece of mitochondrial DNA inserts itself within a gene or regulatory region, it could have important consequences on that person's health or lifespan. Neurons may be particularly susceptible to damage caused by NUMTs because when a neuron is damaged, the brain does not usually make a new brain cell to take its place.

To examine the extent and impact of new NUMTs in the brain, the team worked with Hans Klein, assistant professor in the Center for Translational and Computational Neuroimmunology at Columbia, who had access to DNA sequences from participants in the ROSMAP aging study (led by David Bennett at Rush University). The researchers looked for NUMTs in different regions of the brain using banked tissue samples from more than 1,000 older adults.

Their analysis showed that nuclear mitochondrial DNA insertion happens in the human brain—mostly in the prefrontal cortex—and likely several times over during a person's lifespan.

They also found that people with more NUMTs in their prefrontal cortex died earlier than individuals with fewer NUMTs. "This suggests for the first time that NUMTs may have functional consequences and possibly influence lifespan," Picard says. "NUMT accumulation can be added to the list of genome instability mechanisms that may contribute to aging, functional decline, and lifespan."

Stress accelerates NUMTogenesis

What causes NUMTs in the brain, and why do some regions accumulate more than others?

To get some clues, the researchers looked at a population of human skin cells that can be cultured and aged in a dish over several months, enabling exceptional longitudinal "lifespan" studies.

These cultured cells gradually accumulated several NUMTs per month, and when the cells' mitochondria were dysfunctional from stress, the cells accumulated NUMTs four to five times more rapidly.

"This shows a new way by which stress can affect the biology of our cells," Karan says. "Stress makes mitochondria more likely to release pieces of their DNA and these pieces can then 'infect' the nuclear genome," Zhou adds. It's just one way mitochondria shape our health beyond energy production.

"Mitochondria are cellular processors and a mighty signaling platform," Picard says. "We knew they could control which genes are turned on or off. Now we know mitochondria can even change the nuclear DNA sequence itself."

Reference: "Somatic nuclear mitochondrial DNA insertions are prevalent in the human brain and accumulate over time in fibroblasts" by Weichen Zhou, Kalpita R. Karan, Wenjin Gu, Hans-Ulrich Klein, Gabriel Sturm, Philip L. De Jager, David A. Bennett, Michio Hirano, Martin Picard and Ryan E. Mills, 22 August 2024, PLOS Biology.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.3002723

This work was supported by grants from the U.S. National Institutes of Health (R01AG066828, R21HG011493, and P30AG072931), the Baszucki Brain Research Fund, and the University of Michigan Alzheimer's Disease Center Berger Endowment.

News

Our books now available worldwide!

Online Sellers other than Amazon, Routledge, and IOPP Indigo Global Health Care Equivalency in the Age of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine and Artifcial Intelligence Global Health Care Equivalency In The Age Of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine And Artificial [...]

Scientists Discover Why Some COVID Survivors Still Can’t Taste Food Years Later

A new study provides the first direct biological evidence explaining why some people continue to experience taste loss long after recovering from COVID-19. Researchers have uncovered specific biological changes in taste buds that could help [...]

Catching COVID significantly raises the risk of developing kidney disease, researchers find

Catching Covid significantly raises the risk of developing deadly kidney disease, research has shown. The virus was found to increase the chances that patients will develop the incurable condition by around 50 per cent. [...]

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]

This Simple Brain Exercise May Protect Against Dementia for 20 Years

A long-running study following thousands of older adults suggests that a relatively brief period of targeted brain training may have effects that last decades. Starting in the late 1990s, close to 3,000 older adults [...]

Scientists Crack a 50-Year Tissue Mystery With Major Cancer Implications

Researchers have resolved a 50-year-old scientific mystery by identifying the molecular mechanism that allows tissues to regenerate after severe damage. The discovery could help guide future treatments aimed at reducing the risk of cancer [...]

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]