A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe.

How does your body tell the difference between friendly visitors, like medications and medical devices, and harmful invaders such as viruses and other infectious agents? According to Jacob Brenner, a physician-scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, the answer lies in a protein network that dates back over 500 million years, long before humans and sea urchins evolved along separate paths.

"The complement system is perhaps the oldest-known part of our extracellular immune system," says Brenner. "It plays a crucial role in identifying foreign materials like microbes, medical devices, or new drugs—particularly the larger ones like in the COVID vaccine."

The complement system can act as both protector and aggressor, offering defense on one side while harming the body on the other. In some cases, this ancient network worsens conditions like stroke by mistakenly targeting the body's own tissues. As Brenner explains, when blood vessels leak, complement proteins can reach brain tissue, prompting the immune system to attack healthy cells and leading to worse outcomes for patients.

Now, through a combination of laboratory experiments, coupled differential equations, and computer-based modeling and simulations, an interdisciplinary team from the School of Engineering and Applied Science and the Perelman School of Medicine has uncovered the mathematical principles behind how the complement network "decides" to launch an attack.

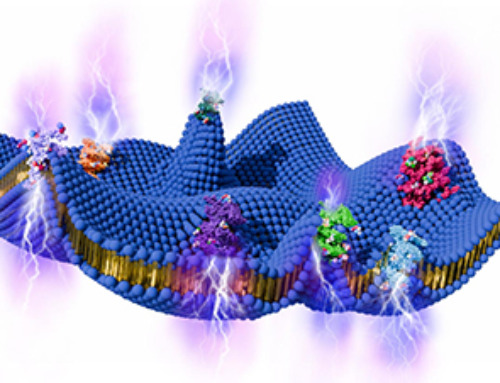

In their study published in Cell, the team identifies a molecular tipping point known as the critical percolation threshold. This threshold depends on how closely complement-binding sites are spaced on the surface of the model invader they designed. If the sites are too far apart, complement activation fades. If they are close enough—below the threshold—it triggers a chain reaction, rapidly recruiting immune agents in a response that spreads like wildfire.

"This discovery enables us to design therapeutics the way you would design a car or a spaceship—using the principles of physics to guide how the immune system will respond—rather than relying on trial and error," says Brenner, who is co-senior author of the study.

Simplifying complexity

While many researchers try to break complex biological systems down into smaller parts such as cells, organelles, and molecules, the team took a different approach. They viewed the system through a mathematical lens, focusing on basic values like density, distance, and speed.

"Not every aspect of biology can be described that way," says co-senior author Ravi Radhakrishnan, bioengineering chair and professor in Penn Engineering. "The complement pathway is fairly ubiquitous across many species and has been preserved through a very long evolutionary time, so we wanted to describe the process using a theory that's universal."

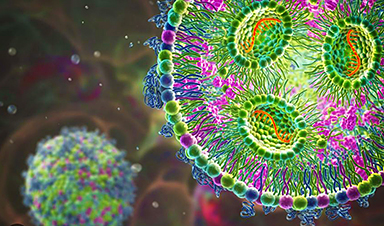

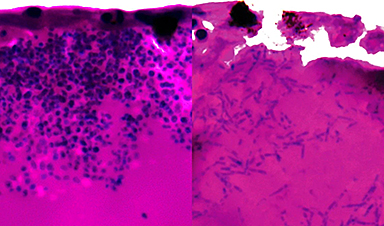

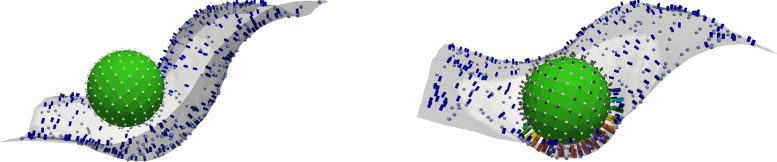

First, a team from Penn Medicine, led by materials scientist Jacob Myerson and nanomedicine research associate Zhicheng Wang, precisely engineered liposomes—tiny, nanoscale fat particles often used as a drug-delivery platform—by studding them with immune-system binding sites. They generated dozens of liposome batches, each with a precisely tuned density of binding sites, and then observed how complement proteins bound and spread in vitro.

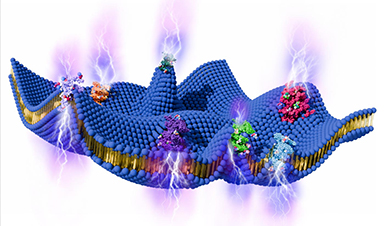

The team then analyzed the experimental data with mathematical tools to assess the binding spread dynamics and immune element recruitment rates and used computational tools to visualize and simulate the reactions to identify when thresholds were being approached.

What they observed in the lab—that closer spacing of proteins ramped up immune activity—became much clearer when viewed through a mathematical lens.

The team's approach drew from complexity science, a field that uses math and physics to study systems with many moving parts. By stripping away the biological specifics, they were able to identify fundamental patterns—like tipping points and phase changes—that explain how the immune system decides when to strike.

"We took that initial observation and then tried to control precisely how closely spaced proteins were on the surface," Myerson says. "We found that there's this threshold spacing that's really the key to understanding how this complement mechanism can turn on or off in response to surface structure."

"If you look only at the molecular details, it's easy to think that every system is unique," adds Radhakrishnan. "But when you model complement mathematically, you see a pattern emerge, not unlike how forest fires spread, or hot water percolates through coffee grounds."

The process of percolation

While much of the research on percolation took place in the 1950s, in the context of petroleum extraction, the physics matched those the researchers observed in complement proteins. "Our system's dynamics map entirely onto the equations of percolation," says Myerson.

Sahil Kulkarni, a doctoral student in Radhakrishnan's lab, not only found that the mathematics of percolation predicted the experimental results that Brenner and Myerson's teams observed, but that complement activation follows a discrete series of steps.

First, an "ignition event" occurs, in which a foreign particle makes contact with the immune system. "It's like an ember falling in a forest," says Kulkarni. "If the trees are spaced too far apart, the fire doesn't spread. But if they're close together, the whole forest burns."

Just like some trees in a forest fire only get singed, percolation theory in the context of biology predicts that not all foreign particles must be fully coated in complement proteins to trigger an immune response. "Some particles are fully engulfed, while others get just a few proteins," Kulkarni explains.

It might seem suboptimal, but that patchiness is likely a feature, not a bug—and one of the chief reasons that evolution selected percolation as the method for activating complement in the first place. It allows the immune system to respond efficiently by coating only "enough" foreign bodies for recognition without overexpending resources or indiscriminately attacking every particle.

Unlike ice formation, which spreads predictably and irreversibly from a single growing crystal, percolation allows for more varied, flexible responses, even ones that can even be reversed. "Because the particles aren't uniformly coated, the immune system can walk it back," adds Kulkarni.

It's also energy efficient. "Producing complement proteins is expensive," says Radhakrishnan. "Percolation ensures you use only what you need."

The next steps along the discovery cascade

Looking ahead, the team is excited to apply their mathematical framework to other complex biological networks such as the clotting cascade and antibody interactions, which rely on similar interactions and dynamics.

"We're particularly interested in applying these methods to the coagulation cascade and antibody interactions," says Brenner. "These systems, like complement, involve dense networks of proteins making split-second decisions, and we suspect they may follow similar mathematical rules."

Additionally, their findings hint at a blueprint for designing safer nanomedicines, Kulkarni notes, explaining how formulation scientists can use this to fine-tune nanoparticles—adjusting protein spacing to avoid triggering complement. This could help reduce immune reactions in lipid-based vaccines, mRNA therapies, and CAR T treatments, where complement activation poses ongoing challenges.

"These kinds of problems live at the intersection of fields," says Myerson. "You need science and engineering know-how to build precision systems, complexity science to reduce 100s of equations modeling each protein-protein interaction to an essential three, and medical professionals who can see the clinical relevance. Investing in team science accelerated these outcomes."

Reference: "A percolation phase transition controls complement protein coating of surfaces" by Zhicheng Wang, Sahil Kulkarni, Jia Nong, Marco Zamora, Alireza Ebrahimimojarad, Elizabeth Hood, Tea Shuvaeva, Michael Zaleski, Damodar Gullipalli, Emily Wolfe, Carolann Espy, Evguenia Arguiri, Jichuan Wu, Yufei Wang, Oscar A. Marcos-Contreras, Wenchao Song, Vladimir R. Muzykantov, Jinglin Fu, Ravi Radhakrishnan, Jacob W. Myerson and Jacob S. Brenner, 13 June 2025, Cell.

DOI: 10.1016/j.cell.2025.05.026

Additional support came from the Pennsylvania Department of Health Research Formula Fund (Award W911NF1910240), the Department of Defense (Grant W911NF2010107), and National Science Foundation (Grant 2215917). Funding was also provided by the Chancellor's Grant for Independent Student Research at Rutgers University–Camden. Instrumentation was supported in part by the Abramson Cancer Center (NCI P30 016520) and Penn Cytomics and Cell Sorting Shared Resource Laboratory (RRID: SCR_022376.)

News

Nanomedicine in 2026: Experts Predict the Year Ahead

Progress in nanomedicine is almost as fast as the science is small. Over the last year, we've seen an abundance of headlines covering medical R&D at the nanoscale: polymer-coated nanoparticles targeting ovarian cancer, Albumin recruiting nanoparticles for [...]

Lipid nanoparticles could unlock access for millions of autoimmune patients

Capstan Therapeutics scientists demonstrate that lipid nanoparticles can engineer CAR T cells within the body without laboratory cell manufacturing and ex vivo expansion. The method using targeted lipid nanoparticles (tLNPs) is designed to deliver [...]

The Brain’s Strange Way of Computing Could Explain Consciousness

Consciousness may emerge not from code, but from the way living brains physically compute. Discussions about consciousness often stall between two deeply rooted viewpoints. One is computational functionalism, which holds that cognition can be [...]

First breathing ‘lung-on-chip’ developed using genetically identical cells

Researchers at the Francis Crick Institute and AlveoliX have developed the first human lung-on-chip model using stem cells taken from only one person. These chips simulate breathing motions and lung disease in an individual, [...]

Cell Membranes May Act Like Tiny Power Generators

Living cells may generate electricity through the natural motion of their membranes. These fast electrical signals could play a role in how cells communicate and sense their surroundings. Scientists have proposed a new theoretical [...]

This Viral RNA Structure Could Lead to a Universal Antiviral Drug

Researchers identify a shared RNA-protein interaction that could lead to broad-spectrum antiviral treatments for enteroviruses. A new study from the University of Maryland, Baltimore County (UMBC), published in Nature Communications, explains how enteroviruses begin reproducing [...]

New study suggests a way to rejuvenate the immune system

Stimulating the liver to produce some of the signals of the thymus can reverse age-related declines in T-cell populations and enhance response to vaccination. As people age, their immune system function declines. T cell [...]

Nerve Damage Can Disrupt Immunity Across the Entire Body

A single nerve injury can quietly reshape the immune system across the entire body. Preclinical research from McGill University suggests that nerve injuries may lead to long-lasting changes in the immune system, and these [...]

Fake Science Is Growing Faster Than Legitimate Research, New Study Warns

New research reveals organized networks linking paper mills, intermediaries, and compromised academic journals Organized scientific fraud is becoming increasingly common, ranging from fabricated research to the buying and selling of authorship and citations, according [...]

Scientists Unlock a New Way to Hear the Brain’s Hidden Language

Scientists can finally hear the brain’s quietest messages—unlocking the hidden code behind how neurons think, decide, and remember. Scientists have created a new protein that can capture the incoming chemical signals received by brain [...]

Does being infected or vaccinated first influence COVID-19 immunity?

A new study analyzing the immune response to COVID-19 in a Catalan cohort of health workers sheds light on an important question: does it matter whether a person was first infected or first vaccinated? [...]

We May Never Know if AI Is Conscious, Says Cambridge Philosopher

As claims about conscious AI grow louder, a Cambridge philosopher argues that we lack the evidence to know whether machines can truly be conscious, let alone morally significant. A philosopher at the University of [...]

AI Helped Scientists Stop a Virus With One Tiny Change

Using AI, researchers identified one tiny molecular interaction that viruses need to infect cells. Disrupting it stopped the virus before infection could begin. Washington State University scientists have uncovered a method to interfere with a key [...]

Deadly Hospital Fungus May Finally Have a Weakness

A deadly, drug-resistant hospital fungus may finally have a weakness—and scientists think they’ve found it. Researchers have identified a genetic process that could open the door to new treatments for a dangerous fungal infection [...]

Fever-Proof Bird Flu Variant Could Fuel the Next Pandemic

Bird flu viruses present a significant risk to humans because they can continue replicating at temperatures higher than a typical fever. Fever is one of the body’s main tools for slowing or stopping viral [...]

What could the future of nanoscience look like?

Society has a lot to thank for nanoscience. From improved health monitoring to reducing the size of electronics, scientists’ ability to delve deeper and better understand chemistry at the nanoscale has opened up numerous [...]