A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight.

Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes of a freshwater apple snail, an animal capable of fully regenerating its vision. Alice Accorsi, assistant professor of molecular and cellular biology at the University of California, Davis, investigates how these snails rebuild their eyes with the long-term goal of applying those lessons to people with eye injuries.

In research published in Nature Communications, Accorsi and her colleagues report that apple snail eyes and human eyes have striking similarities in both anatomy and genetics.

“Apple snails are an extraordinary organism,” said Accorsi. “They provide a unique opportunity to study regeneration of complex sensory organs. Before this, we were missing a system for studying full eye regeneration.”

Her laboratory also created new tools to edit the apple snail genome, opening the door to detailed studies of the genes and molecular pathways that drive eye regrowth.

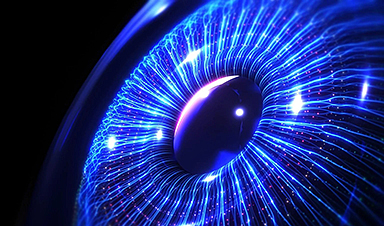

Golden Apple Snail

The golden apple snail has camera-type eyes that are fundamentally similar to the human eye. Unlike humans, the snail can regenerate a missing or damaged eye. UC Davis biologist Alice Accorsi is studying how the snails accomplish this feat. This knowledge could help us understand eye damage in humans and even lead to new ways to heal or regenerate human eyes. Credit: Alice Accorsi, UC Davis

Why the Golden Apple Snail Is a Powerful Research Model

The golden apple snail (Pomacea canaliculata) is native to South America but has spread widely and become invasive in many regions. According to Accorsi, the same traits that allow it to thrive in new environments also make it well-suited for laboratory research.

“Apple snails are resilient, their generation time is very short, and they have a lot of babies,” she said.

They are easy to breed and maintain in controlled settings. Importantly, they possess “camera-type” eyes, the same general eye design found in humans.

Scientists have recognized snails’ regenerative abilities for centuries. In 1766, a researcher documented that decapitated garden snails could regrow their entire heads. Despite that long history, Accorsi is the first to apply this ability specifically to modern regeneration research.

“When I started reading about this, I was asking myself, why isn’t anybody already using snails to study regeneration?” said Accorsi. “I think it’s because we just hadn’t found the perfect snail to study, until now. A lot of other snails are difficult or very slow to breed in the lab, and many species also go through metamorphosis, which presents an extra challenge.”

Camera-Type Eyes in Snails and Humans

Across the animal kingdom, eyes vary widely. Camera-type eyes stand out for producing sharp, high-resolution images. These eyes include a protective cornea, a lens that focuses incoming light, and a retina packed with millions of light-sensitive photoreceptor cells. They are present in all vertebrates, as well as in some spiders, squid, octopi, and certain snails.

Through dissections, advanced microscopy, and genomic studies, Accorsi’s team demonstrated that apple snail eyes closely resemble human eyes in both structure and gene activity.

“We did a lot of work to show that many genes that participate in human eye development are also present in the snail,” Accorsi said. “After regeneration, the morphology and gene expression of the new eye is pretty much identical to the original one.”

How Snails Regrow an Entire Eye

When an apple snail loses an eye, regrowth unfolds in stages over roughly one month. The first step is rapid wound healing to prevent infection and fluid loss, typically completed within 24 hours. Next, undifferentiated cells move into the injured area and begin multiplying. Over the following week and a half, these cells specialize and form essential eye components such as the lens and retina. By day 15 after amputation, all major structures, including the optic nerve, are present. Even then, the eye continues to mature and expand for several additional weeks.

“We still don’t have conclusive evidence that they can see images, but anatomically, they have all the components that are needed to form an image,” said Accorsi. “It would be very interesting to develop a behavioral assay to show that the snails can process stimuli using their new eyes in the same way as they were doing with their original eyes. That’s something we’re working on.”

The researchers also tracked gene activity throughout regeneration. Immediately after amputation, about 9,000 genes showed altered expression compared to normal adult snail eyes. After 28 days, 1,175 genes were still expressed at different levels in regenerated eyes. This suggests that although the eye appears fully formed after a month, its final maturation may take longer at the molecular level.

CRISPR Reveals Genes Behind Eye Development

To pinpoint which genes control regeneration, Accorsi developed CRISPR-Cas9 techniques tailored to apple snails.

“The idea is that we mutate specific genes and then see what effect it has on the animal, which can help us understand the function of different parts of the genome,” said Accorsi.

As an initial experiment, the team used CRISPR/Cas9 to alter a gene called pax6 in snail embryos. Pax6 plays a central role in organizing the brain and eye in humans, mice, and fruit flies. Like humans, snails inherit two copies of each gene, one from each parent. The scientists found that snails with two nonfunctional copies of pax6 developed without eyes, confirming that pax6 is essential for early eye formation in apple snails.

The next phase of research will test whether pax6 is also required for eye regeneration in adults. To answer that question, researchers must switch off or mutate pax6 in mature snails and then assess their ability to regrow eyes.

Accorsi is also examining additional eye-related genes, including those responsible for forming specific structures such as the lens or retina, as well as genes that regulate pax6.

“If we find a set of genes that are important for eye regeneration, and these genes are also present in vertebrates, in theory we could activate them to enable eye regeneration in humans,” said Accorsi.

Reference: “A genetically tractable non-vertebrate system to study complete camera-type eye regeneration” by Alice Accorsi, Brenda Pardo, Eric Ross, Timothy J. Corbin, Melainia McClain, Kyle Weaver, Kym Delventhal, Asmita Gattamraju, Jason A. Morrison, Mary Cathleen McKinney, Sean A. McKinney and Alejandro Sánchez Alvarado, 6 August 2025, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-61681-6

Additional authors on the study are Asmita Gattamraju of UC Davis, Brenda Pardo, Eric Ross, Timothy J. Corbin, Melainia McClain, Kyle Weaver, Kym Delventhal, Jason A. Morrison, Mary Cathleen McKinney, Sean A. McKinney, and Alejandro Sanchez Alvarado of the Stowers Institute for Medical Research. Accorsi performed most of the research for this study at Stowers Institute for Medical Research, where she worked as a postdoctoral fellow before joining UC Davis in 2024.

Funding was provided by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, the Society for Developmental Biology, the American Association for Anatomy and the Stowers Institute for Medical Research.

News

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

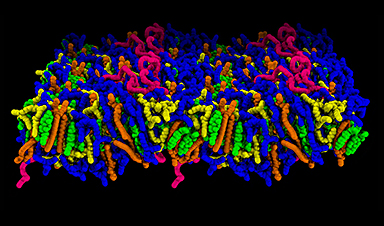

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

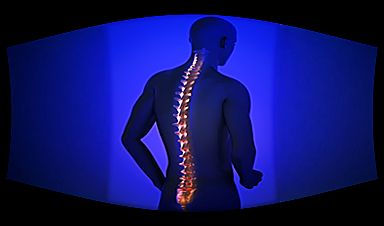

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells

COVID-19 viral fragments shown to target and kill specific immune cells in UCLA-led study Clues about extreme cases and omicron’s effects come from a cross-disciplinary international research team New research shows that after the [...]