Neuroscientists demonstrate how the brain improves its ability to distinguish between similar experiences, findings that could lead to treatments for Alzheimer's disease and other memory disorders.

Think of a time when you had two different but similar experiences in a short period. Maybe you attended two holiday parties in the same week or gave two presentations at work. Shortly afterward, you may find yourself confusing the two, but as time goes on that confusion recedes and you are better able to differentiate between these different experiences.

New research published today (January 19) in Nature Neuroscience reveals that this process occurs on a cellular level, findings that are critical to the understanding and treatment of memory disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease.

Dynamic Engrams Store Memories

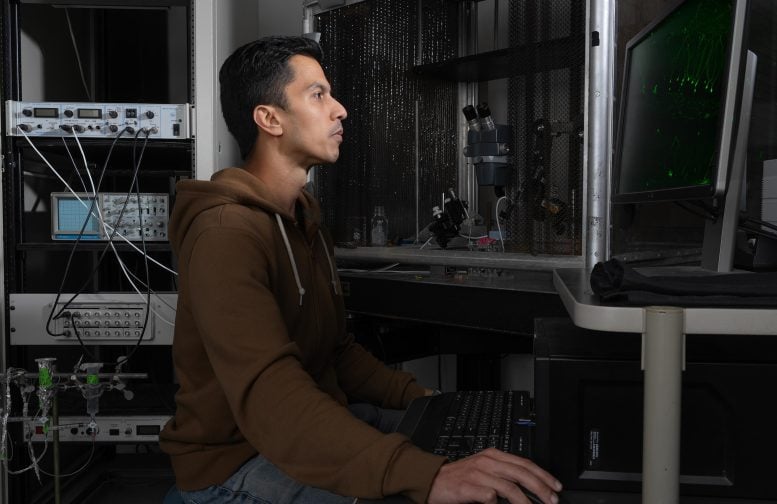

The research focuses on engrams, which are neuronal cells in the brain that store memory information. "Engrams are the neurons that are reactivated to support memory recall," says Dheeraj S. Roy, PhD, one of the paper's senior authors and an assistant professor in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at the University at Buffalo. "When engrams are disrupted, you get amnesia."

In the minutes and hours that immediately follow an experience, he explains, the brain needs to consolidate the engram to store it. "We wanted to know: What is happening during this consolidation process? What happens between the time that an engram is formed and when you need to recall that memory later?"

Dheeraj Roy, PhD, assistant professor in the Department of Physiology and Biophysics in the Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences at UB, is a senior author on a new paper that explains aspects of how memory works at the cellular level. Credit: Sandra Kicman/Jacobs School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences

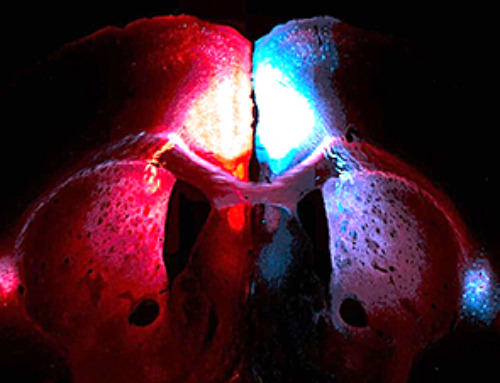

The researchers developed a computational model for learning and memory formation that starts with sensory information, which is the stimulus. Once that information gets to the hippocampus, the part of the brain where memories form, different neurons are activated, some of which are excitatory and others that are inhibitory.

When neurons are activated in the hippocampus, not all are going to be firing at once. As memories form, neurons that happen to be activated closely in time become a part of the engram and strengthen their connectivity to support future recall.

"Activation of engram cells during memory recall is not an all or none process but rather typically needs to reach a threshold (i.e., a percentage of the original engram) for efficient recall," Roy explains. "Our model is the first to demonstrate that the engram population is not stable: The number of engram cells that are activated during recall decreases with time, meaning they are dynamic in nature, and so the next critical question was whether this had a behavioral consequence."

Dynamic Engrams Are Needed for Memory Discrimination

"Over the consolidation period after learning, the brain is actively working to separate the two experiences and that's possibly one reason why the numbers of activated engram cells decrease over time for a single memory," he says. "If true, this would explain why memory discrimination gets better as time goes on. It's like your memory of the experience was one big highway initially but over time, over the course of the consolidation period on the order of minutes to hours, your brain divides them into two lanes so you can discriminate between the two."

Roy and the experimentalists on the team now had a testable hypothesis, which they carried out using a well-established behavioral experiment with mice. Mice were briefly exposed to two different boxes that had unique odors and lighting conditions; one was a neutral environment but in the second box, they received a mild foot shock.

A few hours after that experience, the mice, who typically are constantly moving, exhibited fear memory recall by freezing when exposed to either box. "That demonstrated that they couldn't discriminate between the two," Roy says. "But by hour twelve, all of a sudden, they exhibited fear only when they were exposed to the box where they were uncomfortable during their very first experience. They were able to discriminate between the two. The animal is telling us that they know this box is the scary one but five hours earlier they couldn't do that."

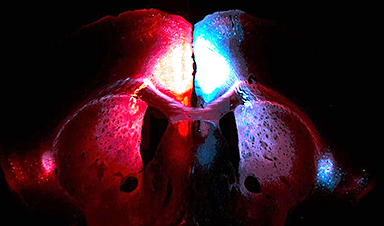

Using a light-sensitive technique, the team was able to detect active neurons in the mouse hippocampus as the animal was exploring the boxes. The researchers used this technique to tag active neurons and later measure how many were reactivated by the brain for recall. They also conducted experiments that allowed a single engram cell to be tracked across experiences and time. "So I can tell you literally how one engram cell or a subset of them responded to each environment across time and correlate this to their memory discrimination," explains Roy."

The team's initial computational studies had predicted that the number of engram cells involved in a single memory would decrease over time, and the animal experiments bore that out.

"When the brain learns something for the first time, it doesn't know how many neurons are needed and so on purpose a larger subset of neurons is recruited," he explains. "As the brain stabilizes neurons, consolidating the memory, it cuts away the unnecessary neurons, so fewer are required and in doing so helps separate engrams for different memories."

What Is Happening With Memory Disorders?

The findings have direct relevance to understanding what is going wrong in memory disorders, such as Alzheimer's disease. Roy explains that to develop treatments for such disorders, it is critical to know what is happening during the initial memory formation, consolidation and activation of engrams for recall.

"This research tells us that a very likely candidate for why memory dysfunction occurs is that there is something wrong with the early window after memory formation where engrams must be changing," says Roy.

He is currently studying mouse models of early Alzheimer's disease to find out if engrams are forming but not being correctly stabilized. Now that more is known about how engrams work to form and stabilize memories, researchers can examine which genes are changing in the animal model when the engram population decreases.

"We can look at mouse models and ask, are there specific genes that are altered? And if so, then we finally have something to test, we can modulate the gene for these 'refinement' or 'consolidation' processes of engrams to see if that has a role in improving memory performance," he says.

Reference: "Dynamic and selective engrams emerge with memory consolidation" 19 January 2024, Nature Neuroscience.

DOI: 10.1038/s41593-023-01551-w

News

This New Blood Test Can Detect Cancer Before Tumors Appear

A new CRISPR-powered light sensor can detect the faintest whispers of cancer in a single drop of blood. Scientists have created an advanced light-based sensor capable of identifying extremely small amounts of cancer biomarkers [...]

Blindness Breakthrough? This Snail Regrows Eyes in 30 Days

A snail that regrows its eyes may hold the genetic clues to restoring human sight. Human eyes are intricate organs that cannot regrow once damaged. Surprisingly, they share key structural features with the eyes [...]

This Is Why the Same Virus Hits People So Differently

Scientists have mapped how genetics and life experiences leave lasting epigenetic marks on immune cells. The discovery helps explain why people respond so differently to the same infections and could lead to more personalized [...]

Rejuvenating neurons restores learning and memory in mice

EPFL scientists report that briefly switching on three “reprogramming” genes in a small set of memory-trace neurons restored memory in aged mice and in mouse models of Alzheimer’s disease to level of healthy young [...]

New book from Nanoappsmedical Inc. – Global Health Care Equivalency

A new book by Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc. Founder. This groundbreaking volume explores the vision of a Global Health Care Equivalency (GHCE) system powered by artificial intelligence and quantum computing technologies, operating on secure [...]

New Molecule Blocks Deadliest Brain Cancer at Its Genetic Root

Researchers have identified a molecule that disrupts a critical gene in glioblastoma. Scientists at the UVA Comprehensive Cancer Center say they have found a small molecule that can shut down a gene tied to glioblastoma, a [...]

Scientists Finally Solve a 30-Year-Old Cancer Mystery Hidden in Rye Pollen

Nearly 30 years after rye pollen molecules were shown to slow tumor growth in animals, scientists have finally determined their exact three-dimensional structures. Nearly 30 years ago, researchers noticed something surprising in rye pollen: [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

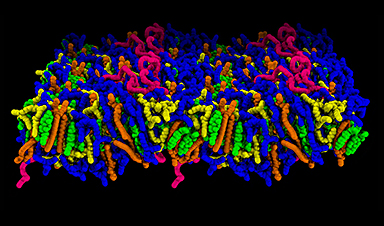

How lipid nanoparticles carrying vaccines release their cargo

A study from FAU has shown that lipid nanoparticles restructure their membrane significantly after being absorbed into a cell and ending up in an acidic environment. Vaccines and other medicines are often packed in [...]

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

A Virus Designed in the Lab Could Help Defeat Antibiotic Resistance

Scientists can now design bacteria-killing viruses from DNA, opening a faster path to fighting superbugs. Bacteriophages have been used as treatments for bacterial infections for more than a century. Interest in these viruses is rising [...]

Sleep Deprivation Triggers a Strange Brain Cleanup

When you don’t sleep enough, your brain may clean itself at the exact moment you need it to think. Most people recognize the sensation. After a night of inadequate sleep, staying focused becomes harder [...]

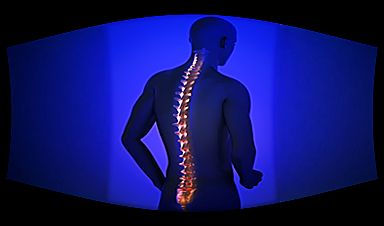

Lab-grown corticospinal neurons offer new models for ALS and spinal injuries

Researchers have developed a way to grow a highly specialized subset of brain nerve cells that are involved in motor neuron disease and damaged in spinal injuries. Their study, published today in eLife as the final [...]

Urgent warning over deadly ‘brain swelling’ virus amid fears it could spread globally

Airports across Asia have been put on high alert after India confirmed two cases of the deadly Nipah virus in the state of West Bengal over the past month. Thailand, Nepal and Vietnam are among the [...]

This Vaccine Stops Bird Flu Before It Reaches the Lungs

A new nasal spray vaccine could stop bird flu at the door — blocking infection, reducing spread, and helping head off the next pandemic. Since first appearing in the United States in 2014, H5N1 [...]

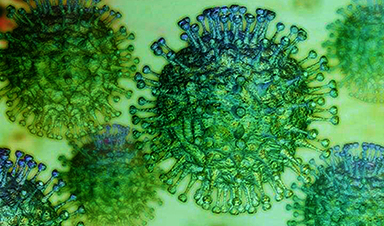

These two viruses may become the next public health threats, scientists say

Two emerging pathogens with animal origins—influenza D virus and canine coronavirus—have so far been quietly flying under the radar, but researchers warn conditions are ripe for the viruses to spread more widely among humans. [...]