A newly identified lymphatic drainage pathway along the middle meningeal artery reveals how the human brain clears waste.

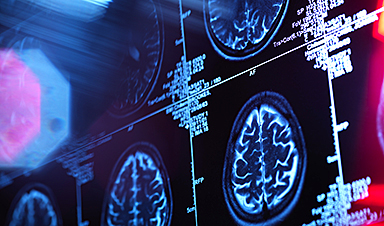

How does the brain clear away waste? This task is handled by the brain's lymphatic drainage system, and attempts to understand how it operates have driven major advances in brain imaging.

A new study published in iScience by researchers at the Medical University of South Carolina reports the first human evidence of a previously unrecognized center of lymphatic drainage in the brain, the middle meningeal artery (MMA).

Using a NASA collaboration that gave them access to real-time MRI tools originally designed to study how spaceflight alters fluid movement in the brain, the MUSC team, led by Onder Albayram, Ph.D., followed the movement of cerebrospinal and interstitial fluids along the MMA in five healthy volunteers over six hours. Their observations showed that cerebrospinal fluid moved slowly and passively, a pattern consistent with lymphatic drainage rather than blood circulation, which would be faster and more pulsatile.

"We saw a flow pattern that didn't behave like blood moving through an artery; it was slower, more like drainage, showing that this vessel is part of the brain's cleanup system," said Albayram, an associate professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at MUSC.

Rethinking the brain's immune isolation

The central nervous system, which includes the brain and spinal cord, is wrapped in a multi-layer protective covering called the meninges. For more than ten years, Albayram has studied meningeal lymphatic vessels, which he believes play a critical role in transporting waste out of the brain and into the body's peripheral lymphatic system, where it can be removed.

Until roughly a decade ago, scientists largely believed that the meninges acted as a barrier separating the brain from the immune system, particularly the lymphatic network. Albayram's research has helped overturn this view by demonstrating that lymphatic vessels are embedded within these membranes and connected to the rest of the body. Gaining a clearer picture of how fluids move between the brain and the periphery is key to expanding strategies for preventing and treating neurological and psychiatric disorders.

Imaging flow from vessels to cells

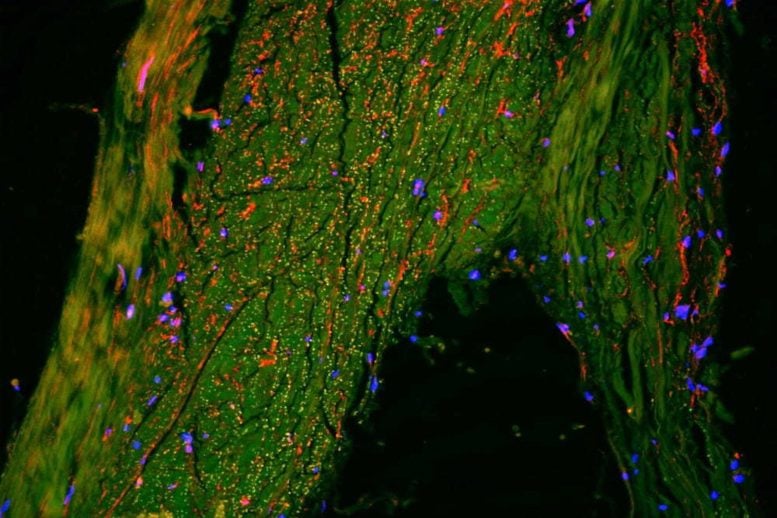

Albayram was among the first to visualize meningeal lymphatic vessels in humans, as reported in a 2022 article in Nature Communications. The study in iScience captures the flow of fluids within the meningeal lymphatic architecture deep within the human brain in real time and validates these findings through advanced imaging of postmortem human tissue.

To confirm what they saw on MRI, Albayram's team examined human brain tissue under extremely high-resolution imaging. Working with scientists at Cornell University, the team used an advanced technique that allows researchers to see many different cell types at once. This detailed mapping showed that the area around the MMA is lined with cells typically found in the body's lymphatic vessels, the channels responsible for clearing waste.

These results confirmed that the slow-moving fluid seen on MRI was indeed flowing through true lymphatic vessels, not blood vessels – linking the brain images directly to cellular evidence.

Why healthy brains matter first

Core to Albayram's work is a focus on making observations in humans first, before expanding out into experimental models, such as mice, rather than the other way around. One key element of this study is that it was conducted in healthy people. Having a clear understanding of how these structures function under normal conditions is essential for recognizing what changes when things go wrong – for example, after a traumatic brain injury or during neurodegenerative conditions.

The implications of this discovery extend to aging, neuroinflammation, brain injury, Alzheimer's disease, and even psychiatric disorders. Albayram is already pursuing research based on key observations of the lymphatic drainage architecture in patients with neurodegenerative diseases, with the goal of developing better ways to diagnose these complex diseases earlier, prevent them, and design new treatments.

"A major challenge in brain research is that we still don't fully understand how a healthy brain functions and ages," said Albayram. "Once we understand what 'normal' looks like, we can recognize early signs of disease and design better treatments."

References:

"Meningeal lymphatic architecture and drainage dynamics surrounding the human middle meningeal artery" by Mehmet Albayram, Sutton B. Richmond, Kaan Yagmurlu, Ibrahim S. Tuna, Eda Karakaya, Hiranmayi Ravichandran, Fatih Tufan, Emal Lesha, Melike Mut, Filiz Bunyak, Yashar.S. Kalani, Adviye Ergul, Rachael D. Seidler and Onder Albayram, 21 November 2025, iScience.

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113693

"Non-invasive MR imaging of human brain lymphatic networks with connections to cervical lymph nodes" by Mehmet Sait Albayram, Garrett Smith, Fatih Tufan, Ibrahim Sacit Tuna, Mehmet Bostancıklıoğlu, Michael Zile and Onder Albayram, 11 January 2022, Nature Communications.

DOI: 10.1038/s41467-021-27887-0

News

A Cambridge Lab Mistake Reveals a Powerful New Way to Modify Drug Molecules

A surprising lab discovery reveals a light-powered way to tweak complex drugs faster, cleaner, and later in development. Researchers at the University of Cambridge have created a new technique for altering complex drug molecules [...]

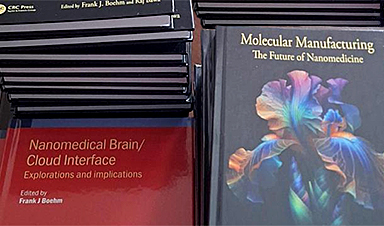

New book from NanoappsMedical Inc – Molecular Manufacturing: The Future of Nanomedicine

This book explores the revolutionary potential of atomically precise manufacturing technologies to transform global healthcare, as well as practically every other sector across society. This forward-thinking volume examines how envisaged Factory@Home systems might enable the cost-effective [...]

Scientists Discover Simple Saliva Test That Reveals Hidden Diabetes Risk

Researchers have identified a potential new way to assess metabolic health using saliva instead of blood. High insulin levels in the blood, known as hyperinsulinemia, can reveal metabolic problems long before obvious symptoms appear. It is [...]

One Nasal Spray Could Protect Against COVID, Flu, Pneumonia, and More

A single nasal spray vaccine may one day protect against viruses, pneumonia, and even allergies. For decades, scientists have dreamed of creating a universal vaccine capable of protecting against many different pathogens. The idea [...]

New AI Model Predicts Cancer Spread With Incredible Accuracy

Scientists have developed an AI system that analyzes complex gene-expression signatures to estimate the likelihood that a tumor will spread. Why do some tumors spread throughout the body while others remain confined to their [...]

Scientists Discover DNA “Flips” That Supercharge Evolution

In Lake Malawi, hundreds of species of cichlid fish have evolved with astonishing speed, offering scientists a rare opportunity to study how biodiversity arises. Researchers have identified segments of “flipped” DNA that may allow fish to adapt rapidly [...]

Our books now available worldwide!

Online Sellers other than Amazon, Routledge, and IOPP Indigo Global Health Care Equivalency in the Age of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine and Artifcial Intelligence Global Health Care Equivalency In The Age Of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine And Artificial [...]

Scientists Discover Why Some COVID Survivors Still Can’t Taste Food Years Later

A new study provides the first direct biological evidence explaining why some people continue to experience taste loss long after recovering from COVID-19. Researchers have uncovered specific biological changes in taste buds that could help [...]

Catching COVID significantly raises the risk of developing kidney disease, researchers find

Catching Covid significantly raises the risk of developing deadly kidney disease, research has shown. The virus was found to increase the chances that patients will develop the incurable condition by around 50 per cent. [...]

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]