Scientists have found a way to fine-tune a central fat-control pathway in the liver, reducing harmful blood triglycerides while preserving beneficial cholesterol functions.

When we eat, the body turns surplus calories into molecules called "triglycerides", especially when those calories come from carbs, sugar, fats, and alcohol. Triglycerides are a type of fat or "lipid", and the body stores them in fat cells to use as fuel between meals.

However, too much of this fat can become harmful. High triglyceride levels can lead to "hypertriglyceridemia" ("excess triglycerides in the blood"), a condition tied to a much higher risk of heart disease, stroke, and pancreatitis. That is why people are widely encouraged to support healthy triglyceride levels through diet and exercise, while more severe cases may require medication.

Dialing down a receptor

Healthy blood fat levels rely on a balance between how much fat enters circulation and how quickly it is removed. The liver and intestine send fat carrying particles into the bloodstream, and enzymes help break them down so the body can clear them. If the body produces more of these fats than it can process, triglycerides accumulate and can contribute to disorders such as dyslipidemia, acute pancreatitis, and metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD).

A key regulator in this network is the Liver X Receptor, or LXR, a protein that controls multiple genes involved in how the body produces and manages fats.

When LXR activity increases, triglycerides and cholesterol often climb as well. Reducing LXR signaling with a drug could be useful, but there is a catch. Because LXR also supports protective cholesterol related pathways in other tissues, shutting it down throughout the body could create unwanted effects. This tradeoff has made it difficult to turn LXR into a safe treatment target.

A drug that specifically targets liver LXR

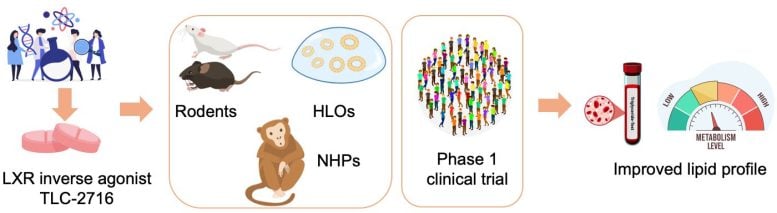

Researchers led by Johan Auwerx at EPFL and Mani Subramanian at OrsoBio have now developed an orally administered compound designed to curb LXR activity mainly in the liver and gut. The goal is to lower triglycerides while leaving the body's protective cholesterol pathways intact.

The drug, TLC-2716, is described as an "inverse agonist" for LXR. Unlike a "blocker" ("antagonist") that simply prevents activation, an "inverse agonist" pushes the receptor toward the reverse of its usual signaling.

The work, published in Nature Medicine, is the first study of this approach to be tested in humans.

Combing genetic datasets to find the right receptor variant

The scientists began by analyzing large human genetics datasets to determine which LXR variant is related to biomarkers for elevated triglycerides in the blood. The data pointed to the genetic variants within LXRα, which is highly expressed in the liver.

This was further confirmed through "Mendelian randomization", a powerful method that determines causal relationships between gene expression and outcomes. In this case, it confirmed a causal link between LXRα and metabolic disorders: higher LXRα expression can drive triglycerides upward.

The findings helped select TLC‑2716 as an effective compound to test against LXRα.

Testing the compound

The study then moved from computers into the lab. In rodent models of metabolic disease, TLC‑2716 and a related compound lowered triglycerides and cholesterol in the blood and reduced fat accumulation in the liver. Meanwhile, experiments in human liver organoids (miniature lab-grown models of diseased liver tissue), showed the same trend, with less lipid buildup and lower inflammation and fibrosis.

Next was safety. Toxicology studies in mice and non-human primates, combined with pharmacokinetic analyses, showed that TLC‑2716 largely stays in the liver and gut. This is key, as it limits exposure to other tissues where inhibiting LXR could be risky, thus addressing the main problem of developing drugs for treating metabolic diseases related to high triglycerides in the body.

The clinical trial

The lab findings set the stage for a randomized, placebo-controlled Phase 1 study in healthy adults. Participants received TLC‑2716 for 14 days, given as a single dose per day, and the trial focused first on safety and tolerability, and the authors report that the drug met these primary endpoints.

But even this short trial had clear effects: participants who received higher doses of TLC‑2716 showed notable drops in triglycerides as well as remnant cholesterol. At the highest doses of TLC‑2716 (12mg), triglycerides fell by up to 38.5%, while postprandial ("after eating") remnant cholesterol dropped by as much as 61%. This happened despite participants starting with relatively normal lipid levels and without the use of other lipid-lowering drugs.

The treatment also sped up triglyceride clearance by reducing the activity of two proteins that normally slow it down, ApoC3 and ANGPTL3. At the same time, the study did not detect reductions in blood-cell expression of ABCA1 and ABCG1, genes used here as markers linked to reverse cholesterol transport.

The trial's results show that selectively reducing LXR activity in the liver and gut by TLC‑2716 may offer a new way, complementary to other approaches, to tackle high triglycerides and related metabolic disorders. The Phase 1 data support further clinical testing in Phase 2 studies, including in people with hypertriglyceridemia and MASLD. Larger trials will be needed, but, for now, the concept has its first human proof of principle.

Reference: "An oral, liver-restricted LXR inverse agonist for dyslipidemia: preclinical development and phase 1 trial" by Xiaoxu Li, Giorgia Benegiamo, Archana Vijayakumar, Natalie Sroda, Masaki Kimura, Ryan S. Huss, Steve Weng, Eisuke Murakami, Brian J. Kirby, Giacomo V. G. von Alvensleben, Claus Kremoser, Edward J. Gane, Takanori Takebe, Robert P. Myers, G. Mani Subramanian and Johan Auwerx, 16 January 2026, Nature Medicine.

DOI: 10.1038/s41591-025-04169-6

Funding: École Polytechnique Fédérale de Lausanne (EPFL), NIH/National Institutes of Health, Japan Agency for Medical Research and Development, Japan World Premier International Research Center Initiative (WPI), OrsoBio

News

One Nasal Spray Could Protect Against COVID, Flu, Pneumonia, and More

A single nasal spray vaccine may one day protect against viruses, pneumonia, and even allergies. For decades, scientists have dreamed of creating a universal vaccine capable of protecting against many different pathogens. The idea [...]

New AI Model Predicts Cancer Spread With Incredible Accuracy

Scientists have developed an AI system that analyzes complex gene-expression signatures to estimate the likelihood that a tumor will spread. Why do some tumors spread throughout the body while others remain confined to their [...]

Scientists Discover DNA “Flips” That Supercharge Evolution

In Lake Malawi, hundreds of species of cichlid fish have evolved with astonishing speed, offering scientists a rare opportunity to study how biodiversity arises. Researchers have identified segments of “flipped” DNA that may allow fish to adapt rapidly [...]

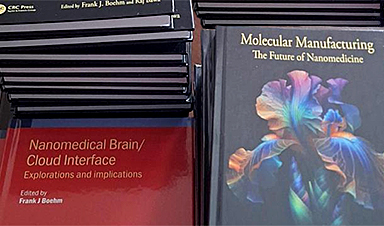

Our books now available worldwide!

Online Sellers other than Amazon, Routledge, and IOPP Indigo Global Health Care Equivalency in the Age of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine and Artifcial Intelligence Global Health Care Equivalency In The Age Of Nanotechnology, Nanomedicine And Artificial [...]

Scientists Discover Why Some COVID Survivors Still Can’t Taste Food Years Later

A new study provides the first direct biological evidence explaining why some people continue to experience taste loss long after recovering from COVID-19. Researchers have uncovered specific biological changes in taste buds that could help [...]

Catching COVID significantly raises the risk of developing kidney disease, researchers find

Catching Covid significantly raises the risk of developing deadly kidney disease, research has shown. The virus was found to increase the chances that patients will develop the incurable condition by around 50 per cent. [...]

New Toothpaste Stops Gum Disease Without Harming Healthy Bacteria

Researchers have developed a targeted approach to combat periodontitis without disrupting the natural balance of the oral microbiome. The innovation could reshape how gum disease is treated while preserving beneficial bacteria. The human mouth [...]

Plastic Without End: Are We Polluting the Planet for Eternity?

The Kunming Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework calls for the elimination of plastic pollution by 2030. If that goal has been clearly set, why have meaningful measures that create real change still not been implemented? [...]

Scientists Rewire Natural Killer Cells To Attack Cancer Faster and Harder

Researchers tested new CAR designs in NK-92 cells and found the modified cells killed tumor cells more effectively, showing stronger anti-cancer activity. Researchers at the Ribeirão Preto Blood Center and the Center for Cell-Based [...]

New “Cellular” Target Could Transform How We Treat Alzheimer’s Disease

A new study from researchers highlights an unexpected player in Alzheimer’s disease: aging astrocytes. Senescent astrocytes have been identified as a major contributor to Alzheimer’s progression. The cells lose protective functions and fuel inflammation, particularly in [...]

Treating a Common Dental Infection… Effects That Extend Far Beyond the Mouth

Successful root canal treatment may help lower inflammation associated with heart disease and improve blood sugar and cholesterol levels. Treating an infected tooth with a successful root canal procedure may do more than relieve [...]

Microplastics found in prostate tumors in small study

In a new study, researchers found microplastics deep inside prostate cancer tumors, raising more questions about the role the ubiquitous pollutants play in public health. The findings — which come from a small study of 10 [...]

All blue-eyed people have this one thing in common

All Blue-Eyed People Have This One Thing In Common Blue Eyes Aren’t Random—Research Traces Them Back to One Prehistoric Human It sounds like a myth at first — something you’d hear in a folklore [...]

Scientists reveal how exercise protects the brain from Alzheimer’s

Researchers at UC San Francisco have identified a biological process that may explain why exercise sharpens thinking and memory. Their findings suggest that physical activity strengthens the brain's built in defense system, helping protect [...]

NanoMedical Brain/Cloud Interface – Explorations and Implications. A new book from Frank Boehm

New book from Frank Boehm, NanoappsMedical Inc Founder: This book explores the future hypothetical possibility that the cerebral cortex of the human brain might be seamlessly, safely, and securely connected with the Cloud via [...]

Deadly Pancreatic Cancer Found To “Wire Itself” Into the Body’s Nerves

A newly discovered link between pancreatic cancer and neural signaling reveals a promising drug target that slows tumor growth by blocking glutamate uptake. Pancreatic cancer is among the most deadly cancers, and scientists are [...]