An international team of scientists, including from the University of Cambridge, have launched a new research collaboration that will leverage the same technology behind ChatGPT to build an AI-powered tool for scientific discovery.

The team launched the initiative, called Polymathic AI earlier this week, alongside the publication of a series of related papers on the arXiv open access repository.

“This will completely change how people use AI and machine learning in science,” said Polymathic AI principal investigator Shirley Ho, a group leader at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics in New York City.

The idea behind Polymathic AI “is similar to how it’s easier to learn a new language when you already know five languages,” said Ho.

Starting with a large, pre-trained model, known as a foundation model, can be both faster and more accurate than building a scientific model from scratch. That can be true even if the training data isn’t obviously relevant to the problem at hand.

“It’s been difficult to carry out academic research on full-scale foundation models due to the scale of computing power required,” said co-investigator Miles Cranmer, from Cambridge’s Department of Applied Mathematics and Theoretical Physics and Institute of Astronomy. “Our collaboration with Simons Foundation has provided us with unique resources to start prototyping these models for use in basic science, which researchers around the world will be able to build from—it’s exciting.”

“Polymathic AI can show us commonalities and connections between different fields that might have been missed,” said co-investigator Siavash Golkar, a guest researcher at the Flatiron Institute’s Center for Computational Astrophysics.

“In previous centuries, some of the most influential scientists were polymaths with a wide-ranging grasp of different fields. This allowed them to see connections that helped them get inspiration for their work. With each scientific domain becoming more and more specialized, it is increasingly challenging to stay at the forefront of multiple fields. I think this is a place where AI can help us by aggregating information from many disciplines.”

“Despite rapid progress of machine learning in recent years in various scientific fields, in almost all cases, machine learning solutions are developed for specific use cases and trained on some very specific data,” said co-investigator Francois Lanusse, a cosmologist at the Center national de la recherche scientifique (CNRS) in France.

“This creates boundaries both within and between disciplines, meaning that scientists using AI for their research do not benefit from information that may exist, but in a different format, or in a different field entirely.”

Polymathic AI’s project will learn using data from diverse sources across physics and astrophysics (and eventually fields such as chemistry and genomics, its creators say) and apply that multidisciplinary savvy to a wide range of scientific problems. The project will “connect many seemingly disparate subfields into something greater than the sum of their parts,” said project member Mariel Pettee, a postdoctoral researcher at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

“How far we can make these jumps between disciplines is unclear,” said Ho. “That’s what we want to do—to try and make it happen.”

ChatGPT has well-known limitations when it comes to accuracy (for instance, the chatbot says 2,023 times 1,234 is 2,497,582 rather than the correct answer of 2,496,382). Polymathic AI’s project will avoid many of those pitfalls, Ho said, by treating numbers as actual numbers, not just characters on the same level as letters and punctuation. The training data will also use real scientific datasets that capture the physics underlying the cosmos.

Transparency and openness are a big part of the project, Ho said. “We want to make everything public. We want to democratize AI for science in such a way that, in a few years, we’ll be able to serve a pre-trained model to the community that can help improve scientific analyses across a wide variety of problems and domains.”

More information: Michael McCabe et al, Multiple Physics Pretraining for Physical Surrogate Models, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2310.02994

Siavash Golkar et al, xVal: A Continuous Number Encoding for Large Language Models, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2310.02989

Francois Lanusse et al, AstroCLIP: Cross-Modal Pre-Training for Astronomical Foundation Models, arXiv (2023). DOI: 10.48550/arxiv.2310.03024

News

The Silent Battle Within: How Your Organs Choose Between Mom and Dad’s Genes

Research reveals that selective expression of maternal or paternal X chromosomes varies by organ, driven by cellular competition. A new study published today (July 26) in Nature Genetics by the Lymphoid Development Group at the MRC [...]

Study identifies genes increasing risk of severe COVID-19

Whether or not a person becomes seriously ill with COVID-19 depends, among other things, on genetic factors. With this in mind, researchers from the University Hospital Bonn (UKB) and the University of Bonn, in [...]

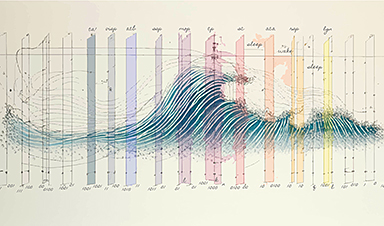

Small regions of the brain can take micro-naps while the rest of the brain is awake and vice versa

Sleep and wake: They're totally distinct states of being that define the boundaries of our daily lives. For years, scientists have measured the difference between these instinctual brain processes by observing brain waves, with [...]

Redefining Consciousness: Small Regions of the Brain Can Take Micro-Naps While the Rest of the Brain Is Awake

The study broadly reveals how fast brain waves, previously overlooked, establish fundamental patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Scientists have developed a new method to analyze sleep and wake states by detecting ultra-fast neuronal activity [...]

AI Reveals Health Secrets Through Facial Temperature Mapping

Researchers have found that different facial temperatures correlate with chronic illnesses like diabetes and high blood pressure, and these can be detected using AI with thermal cameras. They highlight the potential of this technology [...]

Breakthrough in aging research: Blocking IL-11 extends lifespan and improves health in mice

In a recent study published in the journal Nature, a team of researchers used murine models and various pharmacological and genetic approaches to examine whether pro-inflammatory signaling involving interleukin (IL)-11, which activates signaling molecules such [...]

Promise for a universal influenza vaccine: Scientists validate theory using 1918 flu virus

New research led by Oregon Health & Science University reveals a promising approach to developing a universal influenza vaccine—a so-called "one and done" vaccine that confers lifetime immunity against an evolving virus. The study, [...]

New Projects Aim To Pioneer the Future of Neuroscience

One study will investigate the alterations in brain activity at the cellular level caused by psilocybin, the psychoactive substance found in “magic mushrooms.” How do neurons respond to the effects of magic mushrooms? What [...]

Decoding the Decline: Scientific Insights Into Long COVID’s Retreat

Research indicates a significant reduction in long COVID risk, largely due to vaccination and the virus’s evolution. The study analyzes data from over 441,000 veterans, showing lower rates of long COVID among vaccinated individuals compared [...]

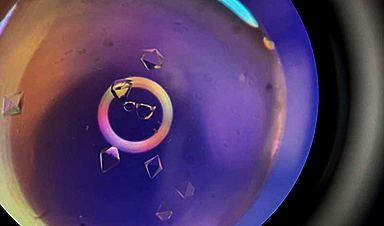

Silicon Transformed: A Breakthrough in Laser Nanofabrication

A new method enables precise nanofabrication inside silicon using spatial light modulation and laser pulses, creating advanced nanostructures for potential use in electronics and photonics. Silicon, the cornerstone of modern electronics, photovoltaics, and photonics, [...]

Caught in the actinium: New research could help design better cancer treatments

The element actinium was first discovered at the turn of the 20th century, but even now, nearly 125 years later, researchers still don't have a good grasp on the metal's chemistry. That's because actinium [...]

Innovative Light-Controlled Drugs Could Revolutionize Neuropathic Pain Treatment

A team of researchers from the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) has developed light-activated derivatives of the anti-epileptic drug carbamazepine to treat neuropathic pain. Light can be harnessed to target drugs to specific [...]

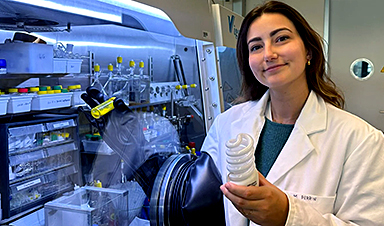

Green Gold: Turning E-Waste Into a Treasure Trove of Rare Earth Metals

Scientists are developing a process inspired by nature that efficiently recovers europium from old fluorescent lamps. The approach could lead to the long-awaited recycling of rare earth metals. A small molecule that naturally serves [...]

Cambridge Study: AI Chatbots Have an “Empathy Gap,” and It Could Be Dangerous

A new study suggests a framework for “Child Safe AI” in response to recent incidents showing that many children perceive chatbots as quasi-human and reliable. A study has indicated that AI chatbots often exhibit [...]

Nanoparticle-based delivery system could offer treatment for diabetics with rare insulin allergy

Up to 3% of people with diabetes have an allergic reaction to insulin. A team at Forschungszentrum Jülich has now studied a method that could be used to deliver the active substance into the [...]

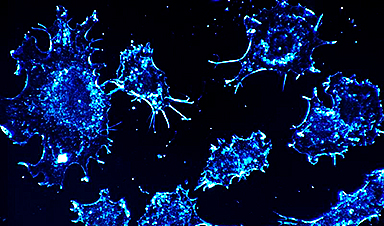

Nanorobot kills cancer cells in mice with hidden weapon

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have developed nanorobots that kill cancer cells in mice. The robot's weapon is hidden in a nanostructure and is exposed only in the tumor microenvironment, sparing healthy cells. [...]