A team of Brown University researchers has developed a new responsive material that is able to release encapsulated cargo only when pathogenic bacteria are present. The material could be used to make wound dressings that respond quickly to burgeoning infections, but only deliver medication on demand.

“We’ve developed a bacteria-triggered, smart drug-delivery system,” said Anita Shukla, an associate professor in Brown’s School of Engineering, who led the material’s development. “Our hypothesis is that technologies like this, which reduce the amount of drug that’s required for effective treatment, can also reduce both side effects and the potential for resistance.”

The new material, described in the journal ACS Applied Materials and Interfaces, is a hydrogel—a hydrated polymer network. Hydrogels are highly biocompatible, and can be used to encapsulate a range of nanoparticles or small molecule therapeutics. They are often used in wound dressings. “Smart” or responsive hydrogels are emerging as promising platforms for drug delivery. They can be made to respond to the localized environment—speeding or slowing the release of medication in response to temperature, pH or other factors.

For this new material, Shukla and her team developed a hydrogel that is sensitive to β-lactamases, a class of enzymes released by a variety of harmful bacteria. The presence of β-lactamases causes the material’s crosslinked polymer network to degrade, releasing the therapeutic nanoparticles held within.

“What’s interesting is that β-lactamases are actually a major cause of antibiotic resistance as they destroy β-lactam antibiotics, which are some of our most commonly prescribed antibiotics,” Shukla said. “But we’ve taken this bacterial defense mechanism and used it against the bacteria.”

In a series of laboratory experiments, Shukla and a team of Brown graduate students showed that the material is indeed sensitive to β-lactamases, releasing nanoparticle cargo only when β-lactamases or β-lactamase-producing bacteria were present. Otherwise, the material kept its cargo encapsulated. The team plans to continue developing and testing the material, eventually in the clinical setting as a wound dressing that can respond to emergent infections.

“We think this is something that does have the potential to be translated to the clinic,” Shukla said. “We’re continuing to work toward that.”

Additional authors on the study are Dahlia Alkekhia and Cassi LaRose from Brown’s Center for Biomedical Engineering.

News

The Silent Battle Within: How Your Organs Choose Between Mom and Dad’s Genes

Research reveals that selective expression of maternal or paternal X chromosomes varies by organ, driven by cellular competition. A new study published today (July 26) in Nature Genetics by the Lymphoid Development Group at the MRC [...]

Study identifies genes increasing risk of severe COVID-19

Whether or not a person becomes seriously ill with COVID-19 depends, among other things, on genetic factors. With this in mind, researchers from the University Hospital Bonn (UKB) and the University of Bonn, in [...]

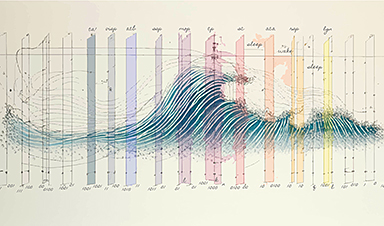

Small regions of the brain can take micro-naps while the rest of the brain is awake and vice versa

Sleep and wake: They're totally distinct states of being that define the boundaries of our daily lives. For years, scientists have measured the difference between these instinctual brain processes by observing brain waves, with [...]

Redefining Consciousness: Small Regions of the Brain Can Take Micro-Naps While the Rest of the Brain Is Awake

The study broadly reveals how fast brain waves, previously overlooked, establish fundamental patterns of sleep and wakefulness. Scientists have developed a new method to analyze sleep and wake states by detecting ultra-fast neuronal activity [...]

AI Reveals Health Secrets Through Facial Temperature Mapping

Researchers have found that different facial temperatures correlate with chronic illnesses like diabetes and high blood pressure, and these can be detected using AI with thermal cameras. They highlight the potential of this technology [...]

Breakthrough in aging research: Blocking IL-11 extends lifespan and improves health in mice

In a recent study published in the journal Nature, a team of researchers used murine models and various pharmacological and genetic approaches to examine whether pro-inflammatory signaling involving interleukin (IL)-11, which activates signaling molecules such [...]

Promise for a universal influenza vaccine: Scientists validate theory using 1918 flu virus

New research led by Oregon Health & Science University reveals a promising approach to developing a universal influenza vaccine—a so-called "one and done" vaccine that confers lifetime immunity against an evolving virus. The study, [...]

New Projects Aim To Pioneer the Future of Neuroscience

One study will investigate the alterations in brain activity at the cellular level caused by psilocybin, the psychoactive substance found in “magic mushrooms.” How do neurons respond to the effects of magic mushrooms? What [...]

Decoding the Decline: Scientific Insights Into Long COVID’s Retreat

Research indicates a significant reduction in long COVID risk, largely due to vaccination and the virus’s evolution. The study analyzes data from over 441,000 veterans, showing lower rates of long COVID among vaccinated individuals compared [...]

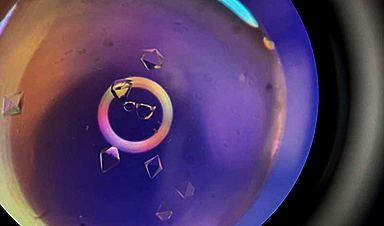

Silicon Transformed: A Breakthrough in Laser Nanofabrication

A new method enables precise nanofabrication inside silicon using spatial light modulation and laser pulses, creating advanced nanostructures for potential use in electronics and photonics. Silicon, the cornerstone of modern electronics, photovoltaics, and photonics, [...]

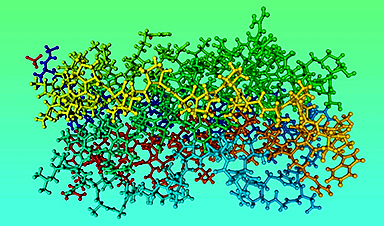

Caught in the actinium: New research could help design better cancer treatments

The element actinium was first discovered at the turn of the 20th century, but even now, nearly 125 years later, researchers still don't have a good grasp on the metal's chemistry. That's because actinium [...]

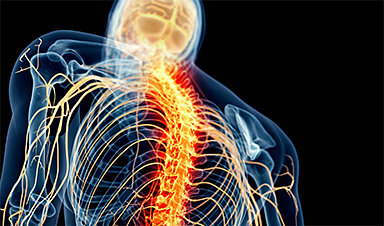

Innovative Light-Controlled Drugs Could Revolutionize Neuropathic Pain Treatment

A team of researchers from the Institute for Bioengineering of Catalonia (IBEC) has developed light-activated derivatives of the anti-epileptic drug carbamazepine to treat neuropathic pain. Light can be harnessed to target drugs to specific [...]

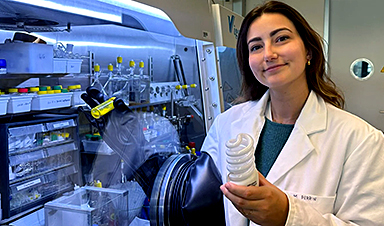

Green Gold: Turning E-Waste Into a Treasure Trove of Rare Earth Metals

Scientists are developing a process inspired by nature that efficiently recovers europium from old fluorescent lamps. The approach could lead to the long-awaited recycling of rare earth metals. A small molecule that naturally serves [...]

Cambridge Study: AI Chatbots Have an “Empathy Gap,” and It Could Be Dangerous

A new study suggests a framework for “Child Safe AI” in response to recent incidents showing that many children perceive chatbots as quasi-human and reliable. A study has indicated that AI chatbots often exhibit [...]

Nanoparticle-based delivery system could offer treatment for diabetics with rare insulin allergy

Up to 3% of people with diabetes have an allergic reaction to insulin. A team at Forschungszentrum Jülich has now studied a method that could be used to deliver the active substance into the [...]

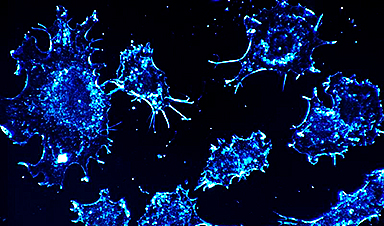

Nanorobot kills cancer cells in mice with hidden weapon

Researchers at Karolinska Institutet in Sweden have developed nanorobots that kill cancer cells in mice. The robot's weapon is hidden in a nanostructure and is exposed only in the tumor microenvironment, sparing healthy cells. [...]