Your breath can give away a lot about you. Each exhalation contains all sorts of compounds, including possible biomarkers for disease or lung conditions, that could give doctors a valuable insight into your health.

Now a new smart mask, developed by a team at the California Institute of Technology, could help doctors check your breath for these signals continuously and in a noninvasive way. A patient could wear the mask at home, measure their own levels, and then go to the doctor if a flare-up is likely.

“They don’t have to come to the clinic to assess their inflammation level,” says Wei Gao, professor of Medical Engineering at Caltech and one of the smart mask’s creators. “This can be lifesaving.”

The smart mask, details of which were published in Science today, uses a two-part cooling system to chill the breath of its wearer. The cooling turns the breath into exhaled breath condensate (EBC).

EBC, essentially a liquid version of someone’s breath, is easier to analyze, because biomarkers like nitrite and alcohol content are more concentrated in a liquid than in a gas. The mask design takes inspiration from plants’ capillary abilities, using a series of microfluidic modules that create pressure to push the EBC fluid around to sensors in the mask.

The sensors are connected via Bluetooth to a device like a phone, where the patient has access to real-time health readings.

“The biggest challenge has always been collecting real-time samples. This problem has been solved. That’s a paradigm shift,” says Rajan Chakrabarty, professor of Environmental and Chemical Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis and who was not involved in the research.

The Caltech team tested the smart mask with patients, including several who had chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma or had just gotten over a covid-19 infection. They were testing the masks for comfort and breathability, but they also wanted to see if the masks actually worked at tracking useful biomarkers throughout a patient’s daily activities, such as exercise and work.

The mask picked up on higher levels of nitrite in patients who had asthma or other conditions that involved inflamed airways. It also picked up on higher alcohol content after a patient went out drinking, which demonstrates another potential application of the mask. Analyzing breath this way is more accurate than the typical breathalyzer test, which involves a patient blowing into a device. Blowing can produce imprecise results due to alcohol in saliva being spit out.

The researchers hope this is just the beginning. They plan to test the masks on a larger population, and if all goes well, commercialize the masks to get them out to a wider audience. They hope the mask will be a platform for broader application, where sensors for a range of biomarkers could be slotted in and out.

“What I would like to be able to do is take off their sensors, put in my sensors, and this becomes the building block for doing all other types of development,” says Albert Titus, professor and chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering at the University at Buffalo and who wasn’t part of the Caltech team. “That’s where I’d like to see it go.”

For example, there may be the possibility to measure ketones in the breath, a high level of which is a sign of diabetes, or glucose levels, to help people with diabetes monitor their condition.

“The mask can be reconfigured for many different applications,” says Gao.

News

Team finds flawed data in recent study relevant to coronavirus antiviral development

The COVID pandemic illustrated how urgently we need antiviral medications capable of treating coronavirus infections. To aid this effort, researchers quickly homed in on part of SARS-CoV-2's molecular structure known as the NiRAN domain—an [...]

Drug-Coated Neural Implants Reduce Immune Rejection

Summary: A new study shows that coating neural prosthetic implants with the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone helps reduce the body’s immune response and scar tissue formation. This strategy enhances the long-term performance and stability of electrodes [...]

Scientists discover cancer-fighting bacteria that ‘soak up’ forever chemicals in the body

A family of healthy bacteria may help 'soak up' toxic forever chemicals in the body, warding off their cancerous effects. Forever chemicals, also known as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), are toxic chemicals that [...]

Johns Hopkins Researchers Uncover a New Way To Kill Cancer Cells

A new study reveals that blocking ribosomal RNA production rewires cancer cell behavior and could help treat genetically unstable tumors. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular [...]

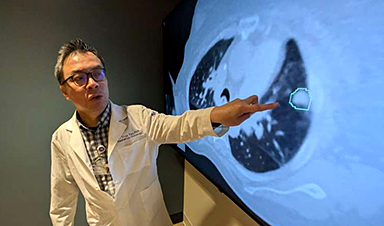

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

Are Pesticides Breeding the Next Pandemic? Experts Warn of Fungal Superbugs

Fungicides used in agriculture have been linked to an increase in resistance to antifungal drugs in both humans and animals. Fungal infections are on the rise, and two UC Davis infectious disease experts, Dr. George Thompson [...]

Scientists Crack the 500-Million-Year-Old Code That Controls Your Immune System

A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe. How does your body [...]

Team discovers how tiny parts of cells stay organized, new insights for blocking cancer growth

A team of international researchers led by scientists at City of Hope provides the most thorough account yet of an elusive target for cancer treatment. Published in Science Advances, the study suggests a complex signaling [...]

Nanomaterials in Ophthalmology: A Review

Eye diseases are becoming more common. In 2020, over 250 million people had mild vision problems, and 295 million experienced moderate to severe ocular conditions. In response, researchers are turning to nanotechnology and nanomaterials—tools that are transforming [...]

Natural Plant Extract Removes up to 90% of Microplastics From Water

Researchers found that natural polymers derived from okra and fenugreek are highly effective at removing microplastics from water. The same sticky substances that make okra slimy and give fenugreek its gel-like texture could help [...]

Instant coffee may damage your eyes, genetic study finds

A new genetic study shows that just one extra cup of instant coffee a day could significantly increase your risk of developing dry AMD, shedding fresh light on how our daily beverage choices may [...]