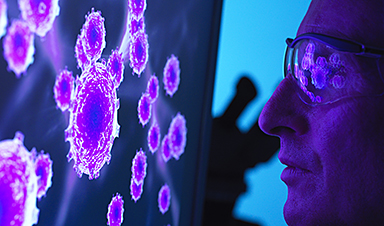

New discoveries about cancer-causing genetic mutations may lead to improved ways of predicting and treating the disease.

Cancer is the second-leading cause of death in the world, including in the United States. In fact, according to the CDC 1.7 million Americans are diagnosed with cancer and 600,000 people die from it each year. Moreover, 1 in 3 people will have cancer in their lifetime. It is a disease caused by an abnormal overgrowth of cells. Now, researchers from the Salk Institute in La Jolla, California have zeroed in on specific mechanisms that activate oncogenes, which are altered genes that can cause normal cells to become cancer cells.

Genetic mutations can cause cancer, yet the impact of specific types, such as structural variants that break and rejoin DNA, can vary widely. Published in the journal Nature on December 7, 2022, the findings show that the activity of those mutations depends on the distance between a particular gene and the sequences that regulate the gene, as well as on the level of activity of the regulatory sequences involved.

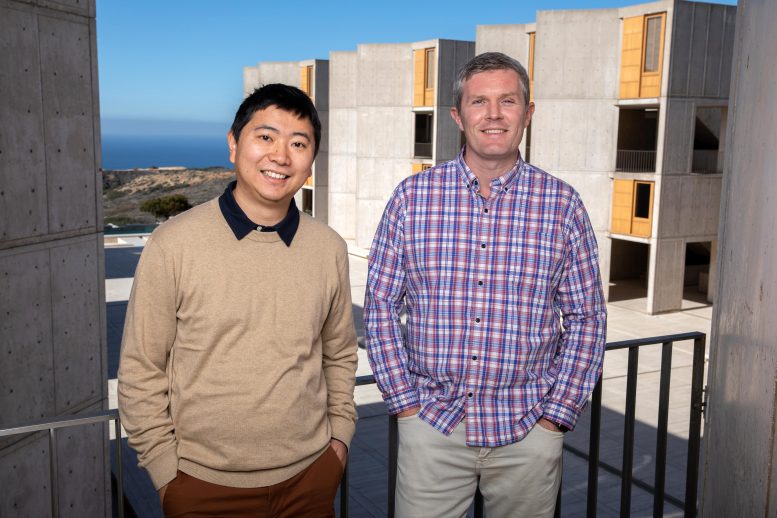

“If we can better understand why a person has cancer, and what particular genetic mutations are driving it, we can better assess risk and pursue new treatments,” says Salk physician-scientist Jesse Dixon, senior author of the paper and an assistant professor in the Gene Expression Laboratory.

Most genetic mutations have no impact on a cancer and the molecular incidents that lead to oncogene activation are relatively rare. Dixon’s lab studies how genomes are organized in 3D space and seeks to understand why these changes happen in some, but not the majority, of circumstances. The team also wants to identify factors that might distinguish where and when these events occur.

“A gene is like a light and what regulates it are like the light switches,” says Dixon. “We are seeing that, because of structural variants in cancer genomes, there are a lot of switches that can potentially turn ‘on’ a particular gene.”

From left: Zhichao Xu and Jesse Dixon. Credit: Salk Institute

“Our next move is to test whether there are other factors in the genome that contribute to the activation of oncogenes,” says Zhichao Xu, a postdoctoral fellow at Salk and the paper’s co-first author. “We are also excited about a new CRISPR genome editing technology we are developing to make this type of genome engineering work much more efficient.”

News

Drug-Coated Neural Implants Reduce Immune Rejection

Summary: A new study shows that coating neural prosthetic implants with the anti-inflammatory drug dexamethasone helps reduce the body’s immune response and scar tissue formation. This strategy enhances the long-term performance and stability of electrodes [...]

Scientists discover cancer-fighting bacteria that ‘soak up’ forever chemicals in the body

A family of healthy bacteria may help 'soak up' toxic forever chemicals in the body, warding off their cancerous effects. Forever chemicals, also known as PFAS (per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances), are toxic chemicals that [...]

Johns Hopkins Researchers Uncover a New Way To Kill Cancer Cells

A new study reveals that blocking ribosomal RNA production rewires cancer cell behavior and could help treat genetically unstable tumors. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular [...]

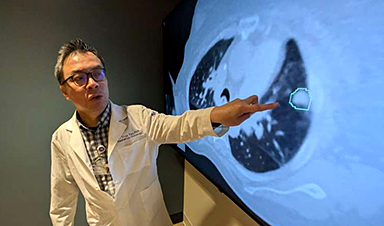

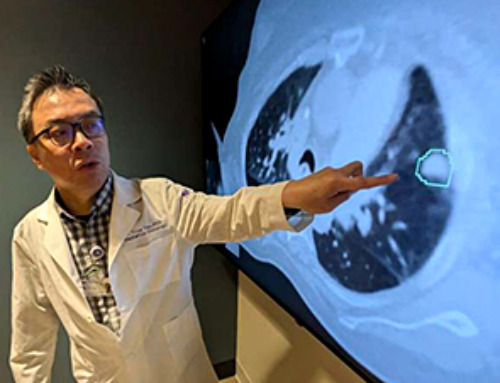

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

Are Pesticides Breeding the Next Pandemic? Experts Warn of Fungal Superbugs

Fungicides used in agriculture have been linked to an increase in resistance to antifungal drugs in both humans and animals. Fungal infections are on the rise, and two UC Davis infectious disease experts, Dr. George Thompson [...]

Scientists Crack the 500-Million-Year-Old Code That Controls Your Immune System

A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe. How does your body [...]

Team discovers how tiny parts of cells stay organized, new insights for blocking cancer growth

A team of international researchers led by scientists at City of Hope provides the most thorough account yet of an elusive target for cancer treatment. Published in Science Advances, the study suggests a complex signaling [...]

Nanomaterials in Ophthalmology: A Review

Eye diseases are becoming more common. In 2020, over 250 million people had mild vision problems, and 295 million experienced moderate to severe ocular conditions. In response, researchers are turning to nanotechnology and nanomaterials—tools that are transforming [...]

Natural Plant Extract Removes up to 90% of Microplastics From Water

Researchers found that natural polymers derived from okra and fenugreek are highly effective at removing microplastics from water. The same sticky substances that make okra slimy and give fenugreek its gel-like texture could help [...]

Instant coffee may damage your eyes, genetic study finds

A new genetic study shows that just one extra cup of instant coffee a day could significantly increase your risk of developing dry AMD, shedding fresh light on how our daily beverage choices may [...]

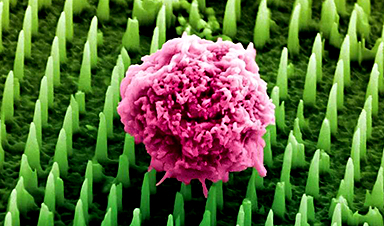

Nanoneedle patch offers painless alternative to traditional cancer biopsies

A patch containing tens of millions of microscopic nanoneedles could soon replace traditional biopsies, scientists have found. The patch offers a painless and less invasive alternative for millions of patients worldwide who undergo biopsies [...]