n June 2021, Israel’s early lead in the world vaccination race seemed to be crumbling. Months earlier it had been the real-world laboratory that showed the effectiveness of vaccines in crushing COVID-19 outbreaks. But now a surge of the faster-moving Delta variant was taking hold, including among the double-jabbed. Data indicated that people vaccinated back in January were more likely to catch COVID than those vaccinated later. Protection from the vaccines seemed to wane after six months.

By September, with new cases topping 10,000 a day, Israel had started rolling out booster shots. At the time, scientists were split over whether a third dose was needed – and the World Health Organisation warned against using up vaccine on boosters while so much of the developing world was still without a single dose.

But, for Israel’s caseload at least, it paid off. The numbers fell again, and studies have since shown that a booster of mRNA sharply lowers the likelihood of COVID infection. With another variant, Omicron, on the loose, the UK, the US, Europe, and now Australia are also turning to boosters, generally six months on from a second dose.

So what does the science say about boosters, why are we mixing and matching vaccine brands and how many more are we likely to need?

Why do we need boosters?

Vaccines teach your body to make special immune cells that can defeat the virus fast if it gets into your system (those are proteins known as antibodies to gum up the virus and killer T-cells to hunt down infected cells). “However healthy your immune system, your body still takes a while to recognise and fight a new threat like [COVID],” says Professor Seshadri Vasan who has spent the pandemic trialling vaccines and tracking coronavirus mutations at the CSIRO’s dangerous-pathogens lab.

Still, this immune memory does fade over time, particularly in older people. Respiratory viruses such as COVID are notoriously difficult to immunise against to begin with, says infectious disease physician Associate Professor Paul Griffin. “We don’t tend to get lifelong protection, even after we catch the common, milder coronaviruses that give us colds. So we always thought we’d need boosters to top up our immunity. What we didn’t know was when.”

The good news is that while people have a higher chance of being infected with COVID six months or more after their second dose, protection against developing a severe case does not decline nearly as fast. To gauge the effectiveness of a vaccine, scientists usually measure antibody levels in someone’s blood. But Griffin says this doesn’t give the complete picture. Antibodies naturally wane over time. “It doesn’t mean the capacity to produce them has gone,” he says. And, while falls in antibody levels may make it easier for a virus to gain a foothold in the body, there will likely still be T cells on the prowl – which are harder to measure but particularly important at stopping severe disease.

In May, Australian researchers calculated that when a vaccinated person’s antibody levels fell to about 20 per cent of their previous level, protection against getting COVID dropped to 50 per cent. But protection against a severe case didn’t fall to 50 per cent until those antibody levels had plunged to just 3 per cent of what they had been.

“The case for boosters is not a failure of the vaccines,” says Griffin. Many existing vaccines need boosters – they both build up antibody levels again and improve the body’s longer-lasting immune defences. COVID boosters can get immunity levels up even higher than where they were two weeks after the second dose.

“The scientific community is actually now debating whether three doses [instead of two] should have been the primary dose schedule all along,” adds Vasan.

When should you have a booster?

Based on both trials and real-world data overseas, Griffin says six months after a second dose has emerged as the standard time to get a booster in Western countries with good access to vaccines such as Australia and the US. (The WHO has yet to recommend widespread boosters.)

As with the original vaccine roll-out, vulnerable groups are at the front of the booster queue. Many Australians with compromised immune systems have had third doses already (at a minimum of two months after their second), and older people and frontline workers who were vaccinated more than six months ago have been getting them too. In November, Australia followed Israel in opening up boosters to every adult six months after their second dose, no matter what vaccine they had already had. As of December 7, 678,154 people were already eligible for an mRNA booster, and, of those, 559,046 had received a third dose of vaccine so far. By the end of the year, 1.75 million people will be eligible and that number will grow to 4.1 million by the end of January, 7.5 million by the end of February before ballooning to 17.8 million by the end of May.

Meanwhile, in places such as the UK, the entire boosters program has been brought forward from six months after your second dose to three as concerns grow that the highly mutated Omicron variant may be better able to evade vaccines. Australia’s expert vaccine advisory group ATAGI considered shortening the interval here too but decided there wasn’t enough evidence that an earlier booster would improve protection against Omicron. The group did advise that the interval could be shortened to five months for logistical reasons, such as for “patients with a greater risk of severe COVID-19 in outbreak settings” but noted this: “There are very limited data on benefit for boosters given prior to 20 weeks after completion of the primary course, and the duration of protection following boosters is not yet known.”

For Australia, where much of the population is still freshly vaccinated, Griffin says waiting the six months will mean many people will be vaccinated around Easter next year right ahead of winter (when the virus may flare up again in the cooler weather). “So I think that’s the right time.”

Are the boosters updated to cover new variants?

Not so far. Vaccine makers have been preparing how best to tweak vaccines for new variants for many months now. But when many existing formulas were found to still work well against the now dominant Delta strain (which emerged in late 2020), regulators approved them as third dose boosters. Some experts have since wondered if that was a missed opportunity but Dr Peter Marks at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in the US, where both Pfizer and Moderna are made, has said that changing formulas only when it is really necessary means less “churn and burn” on manufacturing, and so fewer delays in getting boosters out.

Now, scientists around the world, including Vasan at the CSIRO, are poring over samples of the new variant Omicron to see if a tweak is needed this time. Omicron has about twice as many mutations as the highly infectious Delta, including 34 in the crucial spike protein that the virus uses to hack into our cells. But it is still unclear how that will change its behaviour in patients. Vasan describes it this way: “Just because you might understand individual personality traits, doesn’t mean you can predict exactly how someone will behave. We understand a lot about some of these mutations because we’ve encountered them before in other variants, but Omicron has new ones too, and how they all work together could be different.”

So far, South African doctors report many of the new Omicron cases are mild but the speed at which the new strain has exploded across the continent suggests it is highly infectious. Scientists are particularly concerned the new variant’s spike might have changed shape so much that antibodies can no longer stop it in its tracks (and the WHO has said that reinfection appears more likely with Omicron than Delta). But Vasan adds, “There’s not a one-to-one correlation between the number of mutations and resistance to vaccines.”

The mRNA vaccines are the easiest to adapt, he says. They show our body a tiny segment of the virus’s genetic code (known as RNA) – in this case, the spike protein – to train our immune system to make the right antibodies to fight it if it ever shows up for real.

To tweak the vaccine, scientists just need to swap out the original spike RNA for a mutated Omicron version in its nanoparticle casing. BioNTech, which makes Pfizer, says it can produce and ship an updated version of its vaccine within 100 days if Omicron requires it. But its CEO, Ugur Sahin, has so far been more optimistic about existing vaccines holding up to the variant than the head of Moderna, Stéphane Bancel, who told the Financial Times that he expects to see a “material drop” in vaccine effectiveness against Omicron.

In Australia, tens of millions of the booster doses on order are not expected to arrive until next year, and those may be tweaked if companies such as Pfizer decide that an update against variants is needed. Department of Health secretary Professor Brendan Murphy told a senate committee on December 7 that the country’s contracts already “envisage that if a very different vaccine is required those advance purchase agreements cover that”.

News

Johns Hopkins Researchers Uncover a New Way To Kill Cancer Cells

A new study reveals that blocking ribosomal RNA production rewires cancer cell behavior and could help treat genetically unstable tumors. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular [...]

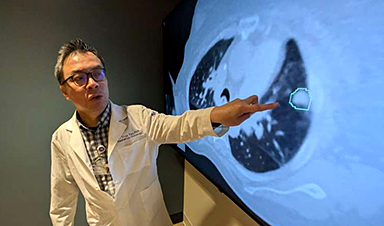

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

Are Pesticides Breeding the Next Pandemic? Experts Warn of Fungal Superbugs

Fungicides used in agriculture have been linked to an increase in resistance to antifungal drugs in both humans and animals. Fungal infections are on the rise, and two UC Davis infectious disease experts, Dr. George Thompson [...]

Scientists Crack the 500-Million-Year-Old Code That Controls Your Immune System

A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe. How does your body [...]

Team discovers how tiny parts of cells stay organized, new insights for blocking cancer growth

A team of international researchers led by scientists at City of Hope provides the most thorough account yet of an elusive target for cancer treatment. Published in Science Advances, the study suggests a complex signaling [...]

Nanomaterials in Ophthalmology: A Review

Eye diseases are becoming more common. In 2020, over 250 million people had mild vision problems, and 295 million experienced moderate to severe ocular conditions. In response, researchers are turning to nanotechnology and nanomaterials—tools that are transforming [...]

Natural Plant Extract Removes up to 90% of Microplastics From Water

Researchers found that natural polymers derived from okra and fenugreek are highly effective at removing microplastics from water. The same sticky substances that make okra slimy and give fenugreek its gel-like texture could help [...]

Instant coffee may damage your eyes, genetic study finds

A new genetic study shows that just one extra cup of instant coffee a day could significantly increase your risk of developing dry AMD, shedding fresh light on how our daily beverage choices may [...]

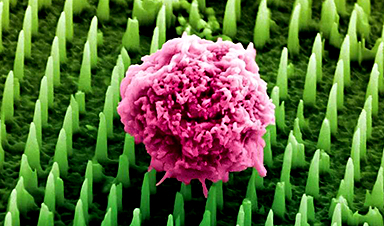

Nanoneedle patch offers painless alternative to traditional cancer biopsies

A patch containing tens of millions of microscopic nanoneedles could soon replace traditional biopsies, scientists have found. The patch offers a painless and less invasive alternative for millions of patients worldwide who undergo biopsies [...]

Small antibodies provide broad protection against SARS coronaviruses

Scientists have discovered a unique class of small antibodies that are strongly protective against a wide range of SARS coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1 and numerous early and recent SARS-CoV-2 variants. The unique antibodies target an [...]

Controlling This One Molecule Could Halt Alzheimer’s in Its Tracks

New research identifies the immune molecule STING as a driver of brain damage in Alzheimer’s. A new approach to Alzheimer’s disease has led to an exciting discovery that could help stop the devastating cognitive decline [...]