Many of the individuals released to long-term acute care facilities suffered from conditions that lasted for over a year.

Researchers at UC San Francisco studied COVID-19 patients in the United States who survived some of the longest and most harrowing battles with the virus. They discovered that approximately two-thirds of these survivors continued to experience a range of physical, psychiatric, and cognitive issues up to a year afterward.

The study, which was recently published in the journal Critical Care Medicine, reveals the life-altering impact of SARS-CoV-2 on these individuals, the majority of whom had to be placed on mechanical ventilators for an average of one month.

Too sick to be discharged to a skilled nursing home or rehabilitation facility, these patients were transferred instead to special hospitals known as long-term acute care hospitals (LTACHs). These hospitals specialize in weaning patients off ventilators and providing rehabilitation care, and they were a crucial part of the pandemic response.

Among the 156 study participants, 64% reported having a persistent impairment after one year, including physical (57%), respiratory (49%), psychiatric (24%), and cognitive (15%). Nearly half, or 47%, had more than one type of problem. And 19% continued to need supplemental oxygen.

The long-term follow-up helps to outline the extent of the medical problems experienced by those who became seriously ill with COVID early in the pandemic.

“We have millions of survivors of the most severe and prolonged COVID illness globally,” said the study’s first author, Anil N. Makam, MD, MAS, an associate professor of medicine at UCSF. “Our study is important to understand their recovery and long-term impairments, and to provide a nuanced understanding of their life-changing experience.”

Disabilities from long-term hospital stays

Researchers recruited 156 people who had been transferred for COVID to one of nine LTACHs in Nebraska, Texas, Georgia, Kentucky, and Connecticut between March 2020 and February 2021. They questioned them by telephone or online a year after their hospitalization. The average total length of stay in the hospital and the LTACH for the group was about two months. Their average age was 65, and most said they had been healthy before getting COVID.

In addition to their lingering ailments from COVID, the participants also had persistent problems from their long hospital stays, including painful bedsores and nerve damage that limited the use of their arms or legs.

“Many of the participants we interviewed were most bothered by these complications, so preventing these from happening in the first place is key to recovery,” Makam said.

Although 79% said they had not returned to their usual health, 99% had returned home, and 60% of those who had previously been employed said they had gone back to work.

They were overwhelmingly grateful to have survived, often describing their survival as a “miracle.” But their recovery took longer than expected.

The results underscore that it is normal to for someone who has survived such severe illness to have persistent health problems.

“The long-lasting impairments we observed are common to survivors of any prolonged critical illness, and not specific to COVID, and are best addressed through multidisciplinary rehabilitation,” Makam said.

Reference: “One-Year Recovery Among Survivors of Prolonged Severe COVID-19: A National Multicenter Cohort” by Anil N. Makam, Judith Burnfield, Ed Prettyman, Oanh Kieu Nguyen, Nancy Wu, Edie Espejo, Cinthia Blat, W. John Boscardin, E. Wesley Ely, James C. Jackson, Kenneth E Covinsky and John Votto, 10 April 2024, Critical Care Medicine.

DOI: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000006258

The work was supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health/National Institute on Aging (K23AG052603), the UCSF Research Evaluation and Allocation Committee (Carson and Hampton Research Funds), and the National Association of Long Term Hospitals. The authors had no conflicts of interest to disclose.

News

Johns Hopkins Researchers Uncover a New Way To Kill Cancer Cells

A new study reveals that blocking ribosomal RNA production rewires cancer cell behavior and could help treat genetically unstable tumors. Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Kimmel Cancer Center and the Department of Radiation Oncology and Molecular [...]

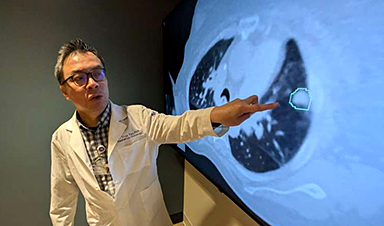

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

Are Pesticides Breeding the Next Pandemic? Experts Warn of Fungal Superbugs

Fungicides used in agriculture have been linked to an increase in resistance to antifungal drugs in both humans and animals. Fungal infections are on the rise, and two UC Davis infectious disease experts, Dr. George Thompson [...]

Scientists Crack the 500-Million-Year-Old Code That Controls Your Immune System

A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe. How does your body [...]

Team discovers how tiny parts of cells stay organized, new insights for blocking cancer growth

A team of international researchers led by scientists at City of Hope provides the most thorough account yet of an elusive target for cancer treatment. Published in Science Advances, the study suggests a complex signaling [...]

Nanomaterials in Ophthalmology: A Review

Eye diseases are becoming more common. In 2020, over 250 million people had mild vision problems, and 295 million experienced moderate to severe ocular conditions. In response, researchers are turning to nanotechnology and nanomaterials—tools that are transforming [...]

Natural Plant Extract Removes up to 90% of Microplastics From Water

Researchers found that natural polymers derived from okra and fenugreek are highly effective at removing microplastics from water. The same sticky substances that make okra slimy and give fenugreek its gel-like texture could help [...]

Instant coffee may damage your eyes, genetic study finds

A new genetic study shows that just one extra cup of instant coffee a day could significantly increase your risk of developing dry AMD, shedding fresh light on how our daily beverage choices may [...]

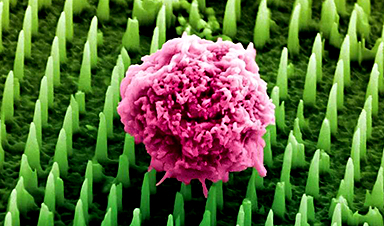

Nanoneedle patch offers painless alternative to traditional cancer biopsies

A patch containing tens of millions of microscopic nanoneedles could soon replace traditional biopsies, scientists have found. The patch offers a painless and less invasive alternative for millions of patients worldwide who undergo biopsies [...]

Small antibodies provide broad protection against SARS coronaviruses

Scientists have discovered a unique class of small antibodies that are strongly protective against a wide range of SARS coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1 and numerous early and recent SARS-CoV-2 variants. The unique antibodies target an [...]

Controlling This One Molecule Could Halt Alzheimer’s in Its Tracks

New research identifies the immune molecule STING as a driver of brain damage in Alzheimer’s. A new approach to Alzheimer’s disease has led to an exciting discovery that could help stop the devastating cognitive decline [...]