| Some researchers are driven by the quest to improve a specific product, like a battery or a semiconductor. Others are motivated by tackling questions faced by a given industry. Rob Macfarlane, MIT’s Paul M. Cook Associate Professor in Materials Science and Engineering, is driven by a more fundamental desire. | |

| “I like to make things,” Macfarlane says. “I want to make materials that can be functional and useful, and I want to do so by figuring out the basic principles that go into making new structures at many different size ranges.” |

| He adds, “For a lot of industries or types of engineering, materials synthesis is treated as a solved problem — making a new device is about using the materials we already have, in new ways. In our lab’s research efforts, we often have to educate people that the reason we can’t do X, Y, or Z right now is because we don’t have the materials needed to enable those technological advances. In many cases, we simply don’t know how to make them yet. This is the goal of our research: Our lab is about enabling the materials needed to develop new technologies, rather than focusing on just the end products.” | |

| By uncovering design principles for nanocomposites, which are materials made from mixtures of polymers and nanoparticles, Macfarlane’s career has gradually evolved from designing specks of novel materials to building functional objects you can hold in your hand. Eventually, he believes his research will lead to new ways of making products with fine-tuned and predetermined combinations of desired electrical, mechanical, optical, and magnetic properties. | |

| Along the way Macfarlane, who earned tenure last year, has also committed himself to mentoring students. He’s taught three undergraduate chemistry courses at MIT, including his current course, 3.010 (Synthesis and Design of Materials), which introduces sophomores to the fundamental concepts necessary for designing and making their own new structures in the future. He also recently redesigned a course in which he teaches graduate students how to be educators by learning how to do things like write a syllabus, communicate with and mentor students, and design homework assignments. | |

| Ultimately, Macfarlane believes mentoring the next generation of researchers is as important as publishing papers. | |

| “I’m fortunate. I’ve been successful, and I have the opportunity to pursue research I’m passionate about,” he says. “Now I view a major component of my job as enabling my students to be successful. The real product and output of what I do here is not just the science and tech advancements and patents, it’s the students that go on to industry or academia or wherever else they choose, and then change the world in their own ways.” | |

From nanometers to millimeters |

|

| Macfarlane was born and raised on a small farm in Palmer, Alaska, a suburban community about 45 minutes north of Anchorage. When he was in high school, the town announced budget cuts that would force the school to scale back a number of classes. In response, Macfarlane’s mother, a former school teacher, encouraged him to enroll in the science education classes that would be offered to students a year older than him, so he wouldn’t miss the chance to take them. | |

| “She knew education was paramount, so she said ‘We’re going to get you into these last classes before they get watered down,’” Macfarlane recalls. | |

| Macfarlane didn’t know any of the students in his new classes, but he had a passionate chemistry teacher that helped him discover a love for the subject. As a result, when he decided to attend Willamette University in Oregon as an undergraduate, he immediately declared himself a chemistry major (which he later adjusted to biochemistry). | |

| Macfarlane attended Yale University for his master’s degree and initially began a PhD there before moving to Northwestern University, where a PhD student’s seminar set Macfarlane on a path he’d follow for the rest of his career. | |

| “[The PhD student] was doing exactly what I was interested in,” says Macfarlane, who asked the student’s PhD advisor, Professor Chad Mirkin, to be his advisor as well. “I was very fortunate when I joined Mirkin’s lab, because the project I worked on had been initiated by a sixth-year grad student and a postdoc that published a big paper and then immediately left. So, there was this wide-open field nobody was working on. It was like being given a blank canvas with a thousand different things to do.” | |

| The work revolved around a precise way to bind particles together using synthetic DNA strands that act like Velcro. | |

| Researchers have known for decades that certain materials exhibit unique properties when assembled at the scale of 1 to 100 nanometers. It was also believed that building things out of those precisely organized assemblies could give objects unique properties. The problem was finding a way to get the particles to bind in a predictable way. | |

| With the DNA-based approach, Macfarlane had a starting point. | |

| “[The researchers] had said, ‘Okay, we’ve shown we can make a thing, but can we make all the things with DNA?’” Macfarlane says. “My PhD thesis was about developing design rules so that if you use a specific set of building blocks, you get a known set of nanostructures as a result. Those rules allowed us to make hundreds of different crystal structures with different sizes, compositions, shapes, lattice structures, etc.” | |

| After completing his PhD, Macfarlane knew he wanted to go into academia, but his biggest priority had nothing to do with work. | |

| “I wanted to go somewhere warm,” Macfarlane says. “I had lived in Alaska for 18 years. I did a PhD in Chicago for six years. I just wanted to go somewhere warm for a while.” | |

| Macfarlane ended up at Caltech in Pasadena, California, working in the labs of Harry Atwater and Nobel laureate Bob Grubbs. Researchers in those labs were studying self-assembly using a new type of polymer, which Macfarlane says required a “completely different” skillset compared to his PhD work. | |

| In 2015, after two years of learning to build materials using polymers and soaking up the sun, Macfarlane plunged back into the cold and joined MIT’s faculty. In Cambridge, Macfarlane has focused on merging the assembly techniques he’s developed for both polymers, DNA, and inorganic nanoparticles to make new materials at larger scales. | |

| That work led Macfarlane and a group of researchers to create a new type of self-assembling building blocks that his lab has dubbed “nanocomposite tectons” (NCTs). NCTs use polymers and molecules that can mimic the ability of DNA to direct the self-organization of nanoscale objects, but with far more scalablility — meaning these materials could be used to build macroscopic objects that can a person can hold in their hand. | |

| “[The objects] had controlled composition at the polymer and nanoparticle level; they had controlled grain sizes and microstructural features; and they had a controlled macroscopic three-dimensional form; and that’s never been done before,” Macfarlane says. “It opened up a huge number of possibilities by saying all those properties that people have been studying for decades on these nanoparticles and their assemblies, now we can actually make them into something functional and useful.” | |

A world of possibilities |

|

| As Macfarlane continues working to make NCTs more scalable, he’s excited about a number of potential applications. | |

| One involves programming objects to transfer energy in specific ways. In the case of mechanical energy, if you hit the object with a hammer or it were involved in a car crash, the resulting energy could dissipate in a way that protects what’s on the other side. In the case of photons or electrons, you could design a precise path for the energy or ions to travel through, which could improve the efficiency of energy storage, computing, and transportation components. | |

| The truth is that such precise design of materials has too many potential applications to count. | |

| Working on such fundamental problems excites Macfarlane, and the possibilities coming from his work will only grow as his team continues to make advances. | |

| “In the end, NCTs open up many new possibilities for materials design, but what might be especially industrially relevant is not so much the NCTs themselves, but what we’ve learned along the way,” Macfarlane says. “We’ve learned how to develop new syntheses and processing methods, so one of the things I’m most excited about is making materials with these methods that have compositions that were previously inaccessible.” |

News

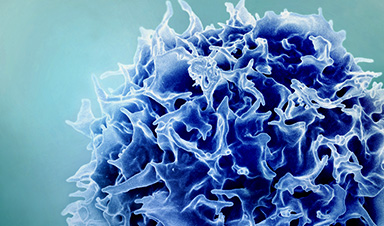

New study suggests a way to rejuvenate the immune system

Stimulating the liver to produce some of the signals of the thymus can reverse age-related declines in T-cell populations and enhance response to vaccination. As people age, their immune system function declines. T cell [...]

Nerve Damage Can Disrupt Immunity Across the Entire Body

A single nerve injury can quietly reshape the immune system across the entire body. Preclinical research from McGill University suggests that nerve injuries may lead to long-lasting changes in the immune system, and these [...]

Fake Science Is Growing Faster Than Legitimate Research, New Study Warns

New research reveals organized networks linking paper mills, intermediaries, and compromised academic journals Organized scientific fraud is becoming increasingly common, ranging from fabricated research to the buying and selling of authorship and citations, according [...]

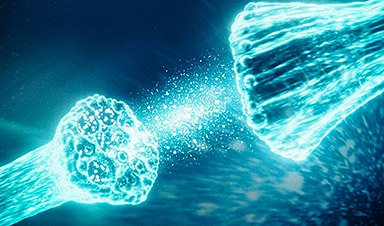

Scientists Unlock a New Way to Hear the Brain’s Hidden Language

Scientists can finally hear the brain’s quietest messages—unlocking the hidden code behind how neurons think, decide, and remember. Scientists have created a new protein that can capture the incoming chemical signals received by brain [...]

Does being infected or vaccinated first influence COVID-19 immunity?

A new study analyzing the immune response to COVID-19 in a Catalan cohort of health workers sheds light on an important question: does it matter whether a person was first infected or first vaccinated? [...]

We May Never Know if AI Is Conscious, Says Cambridge Philosopher

As claims about conscious AI grow louder, a Cambridge philosopher argues that we lack the evidence to know whether machines can truly be conscious, let alone morally significant. A philosopher at the University of [...]

AI Helped Scientists Stop a Virus With One Tiny Change

Using AI, researchers identified one tiny molecular interaction that viruses need to infect cells. Disrupting it stopped the virus before infection could begin. Washington State University scientists have uncovered a method to interfere with a key [...]

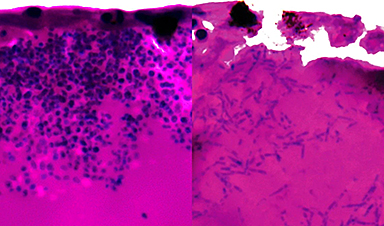

Deadly Hospital Fungus May Finally Have a Weakness

A deadly, drug-resistant hospital fungus may finally have a weakness—and scientists think they’ve found it. Researchers have identified a genetic process that could open the door to new treatments for a dangerous fungal infection [...]

Fever-Proof Bird Flu Variant Could Fuel the Next Pandemic

Bird flu viruses present a significant risk to humans because they can continue replicating at temperatures higher than a typical fever. Fever is one of the body’s main tools for slowing or stopping viral [...]

What could the future of nanoscience look like?

Society has a lot to thank for nanoscience. From improved health monitoring to reducing the size of electronics, scientists’ ability to delve deeper and better understand chemistry at the nanoscale has opened up numerous [...]

Scientists Melt Cancer’s Hidden “Power Hubs” and Stop Tumor Growth

Researchers discovered that in a rare kidney cancer, RNA builds droplet-like hubs that act as growth control centers inside tumor cells. By engineering a molecular switch to dissolve these hubs, they were able to halt cancer [...]

Platelet-inspired nanoparticles could improve treatment of inflammatory diseases

Scientists have developed platelet-inspired nanoparticles that deliver anti-inflammatory drugs directly to brain-computer interface implants, doubling their effectiveness. Scientists have found a way to improve the performance of brain-computer interface (BCI) electrodes by delivering anti-inflammatory drugs directly [...]

After 150 years, a new chapter in cancer therapy is finally beginning

For decades, researchers have been looking for ways to destroy cancer cells in a targeted manner without further weakening the body. But for many patients whose immune system is severely impaired by chemotherapy or radiation, [...]

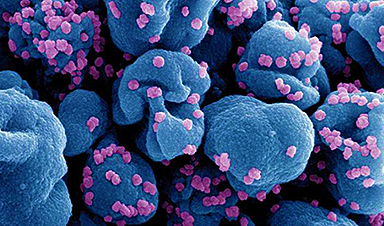

Older chemical libraries show promise for fighting resistant strains of COVID-19 virus

SARS‑CoV‑2, the virus that causes COVID-19, continues to mutate, with some newer strains becoming less responsive to current antiviral treatments like Paxlovid. Now, University of California San Diego scientists and an international team of [...]

Lower doses of immunotherapy for skin cancer give better results, study suggests

According to a new study, lower doses of approved immunotherapy for malignant melanoma can give better results against tumors, while reducing side effects. This is reported by researchers at Karolinska Institutet in the Journal of the National [...]

Researchers highlight five pathways through which microplastics can harm the brain

Microplastics could be fueling neurodegenerative diseases like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's, with a new study highlighting five ways microplastics can trigger inflammation and damage in the brain. More than 57 million people live with dementia, [...]