They call them long-haulers – people still suffering symptoms long after a bout of COVID. But what is the condition, exactly? Doctors expect the answer will change our understanding of immunity forever.

Six months after physiotherapist Scott Willis became one of Australia’s first COVID-19 patients, something strange happened in a swimming pool. One moment he was doing laps, the next he could barely move his arms and legs. “I just ran out of steam. I can pinpoint it to the second,” Willis says. “If I didn’t have the rope to grab on to, if I’d been out in the ocean, what would have happened?”

That bone-deep exhaustion, which can hit suddenly or linger all day, is the most common sign of what has become known as long COVID, in which illness strikes again or drags on months after a COVID-19 infection. But about 200 other symptoms have been linked to it too – sometimes entirely new ones such as confusion and hallucinations, heart palpitations, seizures and sexual dysfunction. So-called long-haulers have likened the condition to “a living death”. Many are too tired to work – or get out of bed.

Millions of people have been affected by long COVID – even many of the clinicians treating it, such as Willis. And that list is only expected to grow. Some researchers expect long COVID cases in Australia to hit 10,000 by the end of the year. Yet, more than two years into the pandemic (and at least 18 months into the condition for Willis), long COVID remains something of a medical mystery.

Is it a new phenomenon or a syndrome like chronic fatigue on a bigger scale? Are some people more at risk of developing the condition than others? What might be going on in the body? And what treatments are being tried?

What is long COVID?

Not long after Willis first fell ill with COVID in Tasmania in early 2020, doctors on the other side of the world, at New York’s Mount Sinai Health Network, noticed something odd. Hospitals had been so overwhelmed during the pandemic’s first wave that Dr David Putrino had set up an app for Mount Sinai doctors to monitor less severe COVID patients remotely, including their oxygen levels. Some were still reporting symptoms months after getting sick.

Putrino says: “People would tell us, ‘Look, I don’t have these acute COVID symptoms any more, but I’m not myself. I’ve got heart palpitations. If I carry my groceries up the stairs, I’m knocked out for two days.’ That was our first inkling long COVID existed.”

Mount Sinai was then setting up a post-COVID recovery hub for patients they expected would need more time to recover – those with lung scarring and other organ damage from a particularly severe infection, or complications from long stays in intensive care. Dr Neha Dangayach, who runs neurological intensive care for Mount Sinai, says: “You can get neurological issues, delirium, or take a long time to bounce back from something like sepsis. But this was something else.”

Most of the patients, particularly those with neurological symptoms, had suffered only mild or moderate cases of COVID-19, and they hadn’t been hospitalised. Often their scans were normal.

As more cases emerged around the world, experts at Mount Sinai and elsewhere began looking for answers – and patients banded together online to share stories and push back against scepticism about the new condition.

Professor Gail Matthews and her colleagues at the Kirby Institute in Sydney were among the first to set up a long-COVID study, at St Vincent’s Hospital. Some patients, she says, will find themselves struggling with just one persistent COVID-19 symptom – a loss of smell and taste, for example. Others show signs their entire nervous system is affected.

COVID presents as a respiratory illness but samples of the virus behind it (SARS CoV-2) have been discovered all over the body – in the lungs, heart and other organs, including, in rare cases, the brain. It can cause clots and stroke, strange rashes, heart, kidney or liver failure, even inflamed, red “COVID toes”. Among survivors, the risk of cardiovascular disease is likely to remain high for months, even years.

Given the virus can affect so much of the body, Matthews says it is perhaps not surprising that long COVID comes with a strange constellation of symptoms too, “though I have found the neurological ones especially surprising”.

In late 2021, the World Health Organisation defined long COVID as occurring in people with “a history of probable or confirmed SARS CoV-2 infection, usually three months from the onset of COVID-19” with symptoms that last for at least two months and cannot be explained by anything else.

Putrino says that with so little understood about the condition, it is right for long COVID to remain a fairly broad church, ranging from those recovering from severe infections to people with sudden neurological symptoms down the road. (In rarer cases, someone may even be affected by both lingering complications and a flare-up of long COVID.)

“We don’t want anyone to fall through the gaps,” he says. “People need insurance cover, access to care. Of course, it also means people might have different treatment [paths]. Some might spontaneously get better, some might not.”

Who is affected by long COVID?

More than 500 million people have now had COVID-19 but no one knows how many long-haulers are among them (some researchers estimate it’s already more than 100 million). So far, while most COVID-19 patients seem to recover, it’s thought that at least 10 to 30 per cent of cases become ongoing – and the risk is about halved if you’re vaccinated. (Recent British data tracking long COVID suggests that fewer than a third of patients fully recover within a year of catching the virus.)

Mount Sinai’s long-COVID clinic has now treated more than 2000 patients, from the bed-bound to the “milder” cases of people who can still work “but they have to lie on the couch all night to recover from the day”, says Putrino. The average age is 45. “In fact, you’re less likely to show up at the clinic if you’re over 65. We don’t know why. And I think that there are a lot of people out there with long-COVID symptoms who don’t know it because they are, fortunately, mild. Some maybe didn’t even know they had COVID.”

Recently, when the hospital was recruiting patients for a clinical trial of those who had fully recovered from COVID, it hit a snag. “Sixty per cent of people who said they had recovered still had symptoms,” says Putrino. “They were like, ‘Oh yeah, I am fatigued, and my heart does beat fast and that never happened before’, whereas only 1 per cent of the control group who had never had COVID failed the symptom screen.”

While you don’t need a severe case of COVID to develop the ongoing condition, one study suggests that having a high viral load (a lot of virus replicating in your system) during your initial infection can push up your risk of long COVID; as can type 2 diabetes, certain “auto-antibodies” that mistakenly attack the body instead of the virus, or a reawakened case of the usually fairly harmless Epstein-Barr virus many people catch in childhood.

There is also a skew towards women in the data. Matthews says: “That could be because women tend to go to the doctor more or because women have different immunology.”

Long COVID can emerge in children too, although as with a regular COVID infection, this is much rarer.

Researchers are not sure if long COVID rates have fluctuated as the virus mutates into different variants, but Putrino says he has found the symptoms fairly consistent between waves. “We’re still getting Delta long COVID into the clinic now. Omicron is only starting.”

Australia, along with many countries, does not track long COVID numbers. But in data released in April by the Australian Bureau of Statistics, 42 of the more than 5000 COVID deaths then officially registered since the pandemic began were considered to be due to long COVID….

News

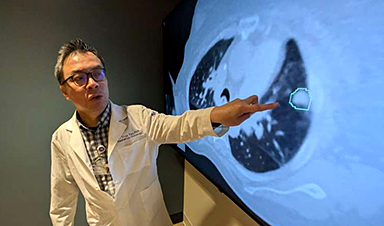

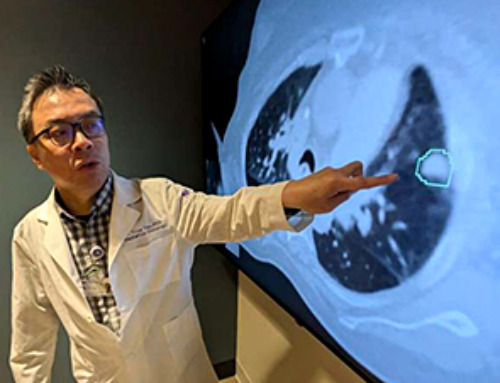

AI matches doctors in mapping lung tumors for radiation therapy

In radiation therapy, precision can save lives. Oncologists must carefully map the size and location of a tumor before delivering high-dose radiation to destroy cancer cells while sparing healthy tissue. But this process, called [...]

Scientists Finally “See” Key Protein That Controls Inflammation

Researchers used advanced microscopy to uncover important protein structures. For the first time, two important protein structures in the human body are being visualized, thanks in part to cutting-edge technology at the University of [...]

AI tool detects 9 types of dementia from a single brain scan

Mayo Clinic researchers have developed a new artificial intelligence (AI) tool that helps clinicians identify brain activity patterns linked to nine types of dementia, including Alzheimer's disease, using a single, widely available scan—a transformative [...]

Is plastic packaging putting more than just food on your plate?

New research reveals that common food packaging and utensils can shed microscopic plastics into our food, prompting urgent calls for stricter testing and updated regulations to protect public health. Beyond microplastics: The analysis intentionally [...]

Aging Spreads Through the Bloodstream

Summary: New research reveals that aging isn’t just a local cellular process—it can spread throughout the body via the bloodstream. A redox-sensitive protein called ReHMGB1, secreted by senescent cells, was found to trigger aging features [...]

AI and nanomedicine find rare biomarkers for prostrate cancer and atherosclerosis

Imagine a stadium packed with 75,000 fans, all wearing green and white jerseys—except one person in a solid green shirt. Finding that person would be tough. That's how hard it is for scientists to [...]

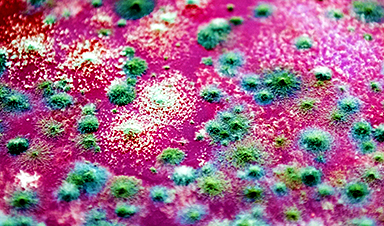

Are Pesticides Breeding the Next Pandemic? Experts Warn of Fungal Superbugs

Fungicides used in agriculture have been linked to an increase in resistance to antifungal drugs in both humans and animals. Fungal infections are on the rise, and two UC Davis infectious disease experts, Dr. George Thompson [...]

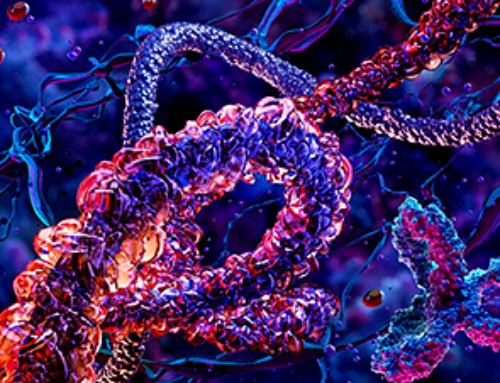

Scientists Crack the 500-Million-Year-Old Code That Controls Your Immune System

A collaborative team from Penn Medicine and Penn Engineering has uncovered the mathematical principles behind a 500-million-year-old protein network that determines whether foreign materials are recognized as friend or foe. How does your body [...]

Team discovers how tiny parts of cells stay organized, new insights for blocking cancer growth

A team of international researchers led by scientists at City of Hope provides the most thorough account yet of an elusive target for cancer treatment. Published in Science Advances, the study suggests a complex signaling [...]

Nanomaterials in Ophthalmology: A Review

Eye diseases are becoming more common. In 2020, over 250 million people had mild vision problems, and 295 million experienced moderate to severe ocular conditions. In response, researchers are turning to nanotechnology and nanomaterials—tools that are transforming [...]

Natural Plant Extract Removes up to 90% of Microplastics From Water

Researchers found that natural polymers derived from okra and fenugreek are highly effective at removing microplastics from water. The same sticky substances that make okra slimy and give fenugreek its gel-like texture could help [...]

Instant coffee may damage your eyes, genetic study finds

A new genetic study shows that just one extra cup of instant coffee a day could significantly increase your risk of developing dry AMD, shedding fresh light on how our daily beverage choices may [...]

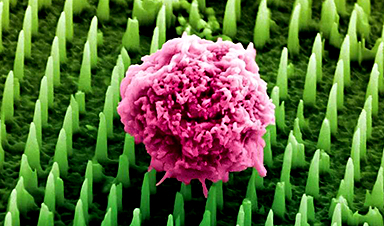

Nanoneedle patch offers painless alternative to traditional cancer biopsies

A patch containing tens of millions of microscopic nanoneedles could soon replace traditional biopsies, scientists have found. The patch offers a painless and less invasive alternative for millions of patients worldwide who undergo biopsies [...]

Small antibodies provide broad protection against SARS coronaviruses

Scientists have discovered a unique class of small antibodies that are strongly protective against a wide range of SARS coronaviruses, including SARS-CoV-1 and numerous early and recent SARS-CoV-2 variants. The unique antibodies target an [...]

Controlling This One Molecule Could Halt Alzheimer’s in Its Tracks

New research identifies the immune molecule STING as a driver of brain damage in Alzheimer’s. A new approach to Alzheimer’s disease has led to an exciting discovery that could help stop the devastating cognitive decline [...]

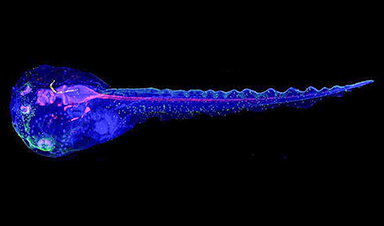

Cyborg tadpoles are helping us learn how brain development starts

How does our brain, which is capable of generating complex thoughts, actions and even self-reflection, grow out of essentially nothing? An experiment in tadpoles, in which an electronic implant was incorporated into a precursor [...]